Sokrates (PR Hrachovec, 2007/08): Unterschied zwischen den Versionen

Aus Philo Wiki

Anna (Diskussion | Beiträge) K (→Die Athenische Verfassung: Gerichtssystem) |

Anna (Diskussion | Beiträge) (→Die Athenische Verfassung: Gerichtssystem 2) |

||

| Zeile 24: | Zeile 24: | ||

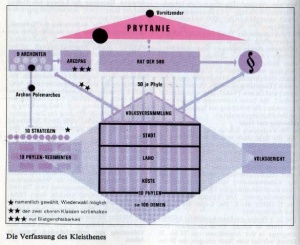

<center>[[Bild:verfassung-kleisthenes.jpeg|thumb|none]]</center> | <center>[[Bild:verfassung-kleisthenes.jpeg|thumb|none]]</center> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <br /> | ||

==== Gerichtssystem ==== | ==== Gerichtssystem ==== | ||

: The cases were put by the litigants themselves in the form of an exchange of single speeches timed by water clock, first prosecutor then defendant. In a public suit the litigants each had three hours to speak, much less in private suits (though here it was in proportion to the amount of money at stake). Decisions were made by voting without any time set aside for deliberation. Nothing, however, stopped jurors from talking informally amongst themselves during the voting procedure and juries could be rowdy shouting out their disapproval or disbelief of things said by the litigants. This may have had some role in building a consensus. The jury could only cast a 'yes' or 'no' vote as to the guilt and sentence of the defendant. For private suits only the victims or their families could prosecute, while for public suits anyone (ho boulomenos, 'whoever wants to' i.e. any citizen with full citizen rights) could bring a case since the issues in these major suits were regarded as affecting the community as a whole. (Wikipedia) | : The cases were put by the litigants themselves in the form of an exchange of single speeches timed by water clock, first prosecutor then defendant. In a public suit the litigants each had three hours to speak, much less in private suits (though here it was in proportion to the amount of money at stake). Decisions were made by voting without any time set aside for deliberation. Nothing, however, stopped jurors from talking informally amongst themselves during the voting procedure and juries could be rowdy shouting out their disapproval or disbelief of things said by the litigants. This may have had some role in building a consensus. The jury could only cast a 'yes' or 'no' vote as to the guilt and sentence of the defendant. For private suits only the victims or their families could prosecute, while for public suits anyone (ho boulomenos, 'whoever wants to' i.e. any citizen with full citizen rights) could bring a case since the issues in these major suits were regarded as affecting the community as a whole. (Wikipedia) | ||

| + | |||

| + | : The system shows a marked anti-professionalism. No judges presided over the courts nor was there anyone to give legal direction to the jurors, as the magistrates in charge of the courts had only an administrative function and were themselves in any case amateurs (most of the annual magistracies at Athens could only be held once in a lifetime). There were no lawyers as such, but the litigants acted solely in their capacity as citizens. Whatever professionalism there was tended to disguise itself: it was possible to pay for the services of a speechwriter (logographos) but this was not advertised in court (except as something your opponent in court has had to resort to), and even politically prominent litigants made some show of disowning special expertise. In many cases in Athens being a Juror was a mark of honor. | ||

Version vom 3. Oktober 2007, 09:10 Uhr

Inhaltsverzeichnis

im Aufbau

Allgemeine Unterlagen

Introduction to Object Oriented Programming through Interactive Fiction

Tutorial: Interactive Fiction am Beispiel von Alice im Wunderland

Die Athenische Verfassung

Gerichtssystem

- The cases were put by the litigants themselves in the form of an exchange of single speeches timed by water clock, first prosecutor then defendant. In a public suit the litigants each had three hours to speak, much less in private suits (though here it was in proportion to the amount of money at stake). Decisions were made by voting without any time set aside for deliberation. Nothing, however, stopped jurors from talking informally amongst themselves during the voting procedure and juries could be rowdy shouting out their disapproval or disbelief of things said by the litigants. This may have had some role in building a consensus. The jury could only cast a 'yes' or 'no' vote as to the guilt and sentence of the defendant. For private suits only the victims or their families could prosecute, while for public suits anyone (ho boulomenos, 'whoever wants to' i.e. any citizen with full citizen rights) could bring a case since the issues in these major suits were regarded as affecting the community as a whole. (Wikipedia)

- The system shows a marked anti-professionalism. No judges presided over the courts nor was there anyone to give legal direction to the jurors, as the magistrates in charge of the courts had only an administrative function and were themselves in any case amateurs (most of the annual magistracies at Athens could only be held once in a lifetime). There were no lawyers as such, but the litigants acted solely in their capacity as citizens. Whatever professionalism there was tended to disguise itself: it was possible to pay for the services of a speechwriter (logographos) but this was not advertised in court (except as something your opponent in court has had to resort to), and even politically prominent litigants made some show of disowning special expertise. In many cases in Athens being a Juror was a mark of honor.