Motive (mse): Unterschied zwischen den Versionen

Anna (Diskussion | Beiträge) K (add content) |

Anna (Diskussion | Beiträge) K (→Die alte Ordnung: pics) |

||

| Zeile 17: | Zeile 17: | ||

== Die alte Ordnung == | == Die alte Ordnung == | ||

| + | |||

| + | {| | ||

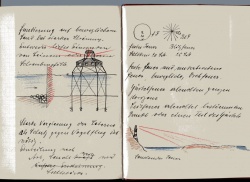

| + | |[[Bild:laurentius_de_voltolina_001-1023x826.jpg|250px]] || [[Bild:Vorlesungsmitschrift.jpeg|250px]] || [[Bild:library-stacks.jpg|250px]] | ||

| + | |} | ||

== Verschwimmen == | == Verschwimmen == | ||

Version vom 4. März 2011, 07:16 Uhr

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Eine verkehrte Welt

Eric A. Havelock: Preface to Plato. Cambridge, Mass. 1963. Harvard University Press. (S.134f)

POETRY, with its rhythms, imagery, and idiom, has in western Europe been prized and practised as a special kind of experience. Viewed in relation to the day's work, the poetic frame of mind is esoteric,and needs artificial cultivation. Over against it there exists the secular cultural situation, which consists of the thought forms and verbal idiom employed in common transactions, in 'affairs' of all kinds. The poetic and the prosaic stand as modes of self-expression which are mutually exclusive. The one is recreation or inspiration, the other is operational. One does not burst into versein order to admonish one's children, or dictate a letter,or tell a joke, still less to give orders or draft directives.

But in the Greek situation, during the non-literate epoch, you might do just that. At least,the gulf between poetic and prosaic could not subsist to the degree it does with us. The whole memory of a people was poetised,and this exercised a constant control over the ways in which they expressed themselves in casual speech.The consequences would go deeper than mere queerness or quaintness (from our standpoint) of verbal idiom. They reach into the problem of the character of the Greek consciousness itself, in a given historical period, the kind of thoughts a Greek could think, and the kind he would not think. The Homeric state of mind was, it will appear, something like a total state of mind.

The argument runs somewhat as follows. In any culture,one discerns two areas of communication: (a) there is the casual and ephemeral converse of daily transaction and (b) there is the area of preserved- communication, which means significantcommunication, which in our culturemeans 'literature', using the word not in an esoteric sense,but to describe the range of experience preserved in books and writings of all kinds, where the ethos and the technology of the culture is preserved. Now, we tend to assume that area (a), being that of the common speech of men, is fundamental, while area (b) is derived from it. But the relationship can be stated in reverse. The idiom and content of area (b),the preserved word, set the formal limits within which the ephemeral word can be expressed. For in area (b)is found the maximum sopllistication of which a given epoch is capable. In short, the books and the bookish tradition of a literate culture set the thought-forms of that culture,and either limit or extend them. Mediaeval scholasticism on the one hand, and modern scientific thought on the other, furnish examples of this law.

In an oral culture, permanent and preserved communication is represented in the saga and its affiliates and only in them. These represent the maximum degree of sophistication. Homer, so far from being 'special', embodies the ruling state of mind. The casual idiom of his epoch which we have lost. should not be assumed to represent a wider and richer range of expression and thought, within which the Homeric vision of the world has formed itself on a special 'poetic' basis. On thecontrary, it is only in preserved and significant speech, with a life of its own, that the maximum of meaning possible to a cultural state of mind is developed. Epic, despite its lightly esoteric vocabulary (actually, because of this vocabulary), represented significant speech, and it had no prosaic competitor. The Homeric state of mind was therefore, it could be said, the general state of mind.

Die alte Ordnung

|

|

|

Verschwimmen

Bruchstellen

Sprechen

<videoflash type="youtube">lhf_hMCaV3o|200|180</videoflash>

Schreiben

Mixen

Orientierungspunkte

Gesang

Ilias 494 ff

Führer war den Böoten Peneleos, Leïtos Führer, Arkesilaos zugleich, und Klonios, samt Prothoenor. Alle, die Hyrie rings, und die felsige Aulis bewohnten, Schönos auch, und Skolos, und weit die Höhn Eteonos, Dann Thespeia, und Gräa, und weit die Aun Mykalessos; Auch die Harma umwohnten, Eilesion auch, und Erythrä, Auch die Eleon sich, und Peteon bauten, und Hyle, Rings Okalea dann, und Medeons prangende Gassen, Kopä, samt Eutresis, und Thisbe, flatternd von Tauben; Die Koroneia umher, und die Grasgefild' Haliartos, Die Platäa gebaut, und die in Glissas gewohnet, Die umher Hypothebe bewohnt in prangenden Häusern, Auch Onchestos lieblichen Hain um den Tempel Poseidons; Die dann Arne bewohnt voll Weinhöhn, auch die Mideia, Auch die heilige Nissa, und fern Anthedon die Grenzstadt: Diese zogen daher in fünfzig Schiffen, und jedes Trug der böotischen Jugend erlesene hundert und zwanzig. Die in Orchomenos wohnten, der Minyer, und in Aspledon, Führt' Askalaphos an, und Ialmenos, Söhne des Ares, Aus der Astyoche Schoß: in der Burg des azeidischen Aktors Stieg sie einst in den Söller empor, die schüchterne Jungfrau, Hin zum gewaltigen Ares, und sank in geheimer Umarmung. Diese trug ein Geschwader von dreißig gebogenen Schiffen.

Pirron und Knapp

<flashmp3>http://131.130.46.67/wiki_stuff/camping.mp3</flashmp3>