Roland Barthes (mse): Unterschied zwischen den Versionen

Aus Philo Wiki

Anna (Diskussion | Beiträge) K (→Roland Barthes: content) |

Anna (Diskussion | Beiträge) K (→Die Rauheit der Stimme: content) |

||

| Zeile 20: | Zeile 20: | ||

== Die Rauheit der Stimme == | == Die Rauheit der Stimme == | ||

| − | http://openlibrary.org/books/OL22647063M/Le_grain_de_la_voix | + | === http://openlibrary.org/books/OL22647063M/Le_grain_de_la_voix === |

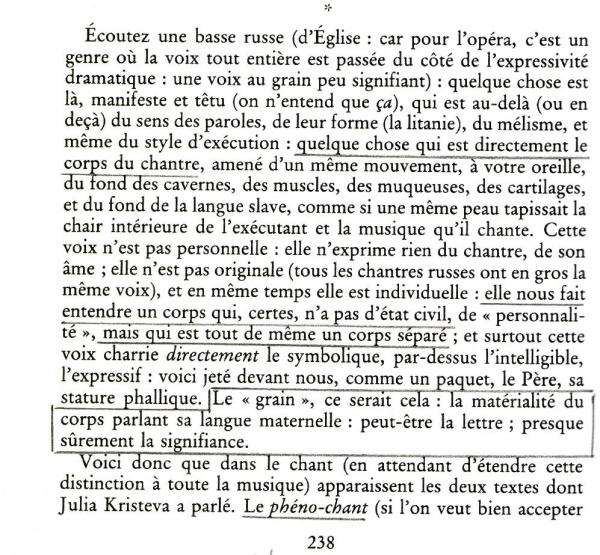

[[Bild:barthes-grain1.JPG |600px|center]] | [[Bild:barthes-grain1.JPG |600px|center]] | ||

| Zeile 26: | Zeile 26: | ||

[[Bild:barthes-grain2.JPG |600px|center]] | [[Bild:barthes-grain2.JPG |600px|center]] | ||

| − | [http://www.sysx.org/soundsite/texts/02/VOICE.html Kate Callaghan: Some thoughts on voice and modes of listening] | + | |

| + | === [http://www.sysx.org/soundsite/texts/02/VOICE.html Kate Callaghan: Some thoughts on voice and modes of listening] === | ||

| + | |||

| + | :I am particularly interested, though, in the microperceptual, which explains to me why sound and musics are so irrevocably tied to the body in Western culture. To hear is to connect with our "bodily position", with what we can sense, because we cannot perceive sound without both time and space. I understand that somehow our assumption and experience of sound’s emotional power rests in its happening in time and space. Just as we imagine our existence to be in both body (time) and soul (space), so sound makes a linkage between them real for us. Just as our person is both concrete and imagined, so is sound. Conversely, silence is equated to death, to absolute Otherness. However, as we have seen, silence perceived is actually sound. And if sound is a phenomenon that occurs and decays over time and space, ever decreasing in intensity, then the human body could also be described in such a way. Whereas we only have to close our eyes to cut off sight, we can only cut off hearing through death, and so sound and musics tied mortality. Because sound decays, it gives us a sense of being there at its vortex, or not being there. Like the human body a decaying sound - a sound moving toward silence - moves into a distance that is marked by its absence from itself. A colloquialism - peace and quiet - demonstrates our culture’s equation of spiritual peacefulness~state of calm~accepting with quietness~absence~death. We begin to see how sound is written on the body, or rather, resonates in and through the body. I find it interesting that Barthes’ experience of Schumann could equally apply to late twentieth century dance music: the beat or rhythm is "whatever makes any site of the body flinch" (Barthes 1985, 304), this is how we can designate a "dance music" a such, and how it can connect to the "beating body" (Barthes 1985, 310). It is perhaps no coincidence that this kind of music, so connected with it audience’s "beating body" generally employs two fundamentals: a pitched voice/tune (nervous system) and a (usually unpitched) bass/beat (blood in circulation). That is, Cage’s minimum number of sounds, the embodied essentials. This may be as close as we can get to a "primal sound" (Rilke: 53). "My body is to the greatest extent what everything is": and so too sound (Merleau-Ponty, The Visible and the Invisible quoted in Andrews: 6). The recognition of sound as a linkage of time and space - where in Western culture we have traditionally tried to separate, and valorise one over the other - automatically provides the possibility of a linkage between many "opposites", mind~body~spirit, conscious~unconscious, me~you, us~them. No wonder then the microperceptual requires a macroperceptual to acculturate the unheard and consequently reinstate it’s "natural" philosophical boundaries! | ||

| + | |||

| + | ... | ||

| + | |||

| + | :Roland Barthes named this individual voice-magic the grain of the voice. The grain is imparted in the "very precise space of the encounter between a language and a voice" (Barthes 1977, 181). In this sense, the voice is "pure indication", pure meaning to mean, pure universal transcendence (Agamben: 32). But where is the place of the voice if the hearer does not understand the language is question? The expectation of a contemporary opera audience hangs on exactly this assumption - that the grain of the voice will carry enough meaning to the ear, so that we do not need to understand the Italian/German/French/Russian. "The more the word is known, but not fully known, the more the mind desires to know the rest " (Augustine, quoted in Agamben: 292-3). Augustine equates this desire with the desire for knowledge: interesting since I pose that voice, by facilitating language, bridges the gap between microperception (phenomenological knowledge) and macroperception (cultural knowledge), between experience and thought. But the listener in this and the operatic case must accept that there is something in the grain of the voice which carries meaning between the signifier and the signified. | ||

| + | |||

| + | :If this space between the sound and its meaning, or between our micro and macro perceptions of it "opens a new field of though [and]...is, therefore, singularly close to the field of meaning of pure being", it has been articulated via a body and its breath/spirit/voice (Agamben: 34). No wonder then, it is difficult to listen to or for this space in the Others voice, the "unheard of". Perhaps it is here that we begin to understand the connection between language (sound) and death. For if to experience is to comprehend, then to comprehend the space of "pure being" in a voice is also to experience its complete Otherness. It is to experience in real time the gap between the word and its sounding (Dyson 1995, 40-46). The voice of an animal certainly places it, but can in no way realise that moment of discourse (Agamben: 35), hence the essential relation between death and language flashes up before us... | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

[http://homepages.uni-paderborn.de/winkler/pop.html Hartmut Winkler, Ulrike Bergermann: Singende Maschinen und resonierende Körper] | [http://homepages.uni-paderborn.de/winkler/pop.html Hartmut Winkler, Ulrike Bergermann: Singende Maschinen und resonierende Körper] | ||

Version vom 23. Juni 2011, 16:35 Uhr

| 200|180</videoflash> | 200|180</videoflash> | 200|180</videoflash> | 200|180</videoflash> |

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Harvey Goldberg

| <flashmp3>http://131.130.46.67/wiki_stuff/goldberg-mitbestimmung2.mp3</flashmp3> | Harvey Goldberg über Arbeitermitbestimmung in Deutschland |

Roland Barthes

Die Rauheit der Stimme

http://openlibrary.org/books/OL22647063M/Le_grain_de_la_voix

Kate Callaghan: Some thoughts on voice and modes of listening

- I am particularly interested, though, in the microperceptual, which explains to me why sound and musics are so irrevocably tied to the body in Western culture. To hear is to connect with our "bodily position", with what we can sense, because we cannot perceive sound without both time and space. I understand that somehow our assumption and experience of sound’s emotional power rests in its happening in time and space. Just as we imagine our existence to be in both body (time) and soul (space), so sound makes a linkage between them real for us. Just as our person is both concrete and imagined, so is sound. Conversely, silence is equated to death, to absolute Otherness. However, as we have seen, silence perceived is actually sound. And if sound is a phenomenon that occurs and decays over time and space, ever decreasing in intensity, then the human body could also be described in such a way. Whereas we only have to close our eyes to cut off sight, we can only cut off hearing through death, and so sound and musics tied mortality. Because sound decays, it gives us a sense of being there at its vortex, or not being there. Like the human body a decaying sound - a sound moving toward silence - moves into a distance that is marked by its absence from itself. A colloquialism - peace and quiet - demonstrates our culture’s equation of spiritual peacefulness~state of calm~accepting with quietness~absence~death. We begin to see how sound is written on the body, or rather, resonates in and through the body. I find it interesting that Barthes’ experience of Schumann could equally apply to late twentieth century dance music: the beat or rhythm is "whatever makes any site of the body flinch" (Barthes 1985, 304), this is how we can designate a "dance music" a such, and how it can connect to the "beating body" (Barthes 1985, 310). It is perhaps no coincidence that this kind of music, so connected with it audience’s "beating body" generally employs two fundamentals: a pitched voice/tune (nervous system) and a (usually unpitched) bass/beat (blood in circulation). That is, Cage’s minimum number of sounds, the embodied essentials. This may be as close as we can get to a "primal sound" (Rilke: 53). "My body is to the greatest extent what everything is": and so too sound (Merleau-Ponty, The Visible and the Invisible quoted in Andrews: 6). The recognition of sound as a linkage of time and space - where in Western culture we have traditionally tried to separate, and valorise one over the other - automatically provides the possibility of a linkage between many "opposites", mind~body~spirit, conscious~unconscious, me~you, us~them. No wonder then the microperceptual requires a macroperceptual to acculturate the unheard and consequently reinstate it’s "natural" philosophical boundaries!

...

- Roland Barthes named this individual voice-magic the grain of the voice. The grain is imparted in the "very precise space of the encounter between a language and a voice" (Barthes 1977, 181). In this sense, the voice is "pure indication", pure meaning to mean, pure universal transcendence (Agamben: 32). But where is the place of the voice if the hearer does not understand the language is question? The expectation of a contemporary opera audience hangs on exactly this assumption - that the grain of the voice will carry enough meaning to the ear, so that we do not need to understand the Italian/German/French/Russian. "The more the word is known, but not fully known, the more the mind desires to know the rest " (Augustine, quoted in Agamben: 292-3). Augustine equates this desire with the desire for knowledge: interesting since I pose that voice, by facilitating language, bridges the gap between microperception (phenomenological knowledge) and macroperception (cultural knowledge), between experience and thought. But the listener in this and the operatic case must accept that there is something in the grain of the voice which carries meaning between the signifier and the signified.

- If this space between the sound and its meaning, or between our micro and macro perceptions of it "opens a new field of though [and]...is, therefore, singularly close to the field of meaning of pure being", it has been articulated via a body and its breath/spirit/voice (Agamben: 34). No wonder then, it is difficult to listen to or for this space in the Others voice, the "unheard of". Perhaps it is here that we begin to understand the connection between language (sound) and death. For if to experience is to comprehend, then to comprehend the space of "pure being" in a voice is also to experience its complete Otherness. It is to experience in real time the gap between the word and its sounding (Dyson 1995, 40-46). The voice of an animal certainly places it, but can in no way realise that moment of discourse (Agamben: 35), hence the essential relation between death and language flashes up before us...

Hartmut Winkler, Ulrike Bergermann: Singende Maschinen und resonierende Körper

Stimmlose Sprache?

http://userpage.fu-berlin.de/~sybkram/media/downloads/Negative_Semiologie_der_Stimme.pdf Sybille Krämer: Negative Semiologie der Stimme (passim)

- Rekapitulieren wir noch einmal die Besonderheiten der Stimmlichkeit:

- Im Fluxus des Sprechens verkörpert die Stimme Ereignishaftigkeit; die Aisthesis des gesprochenen Wortes ist von irreduzibler Singularität.

- Als vollzogener Machtgestus oder als Reflex gefühlter Ohnmacht, als eindringlicher und aufdringlicher Anspruch an den anderen, ist das Register der Stimme verwoben mit einem Typus der Zwischenmenschlichkeit, dessen Nährboden weniger das Argumentieren, denn der Affekt ist.

- Als Teil der elementaren wie existentialen Leiblichkeit der Sprecher zeugt die Stimme immer auch von unserer Bedürftigkeit, der ein Begehren eigen ist, das sich an den anderen richtet. In unserer Stimmlichkeit werden wir nicht nur als ‚Essenzen‘, vielmehr als konkret situierte leibliche ‚Existenzen‘ offenbar.

- Wenn aber in der Stimme sich eine macht- und ohnmachtbezogene Form von Intersubjektivität, ein gefühlsmäßiges Gestimmtsein jenseits kognitiver Dispositionen, eine aisthetische Kraft, die nicht dem Logos zu Diensten ist, artikuliert, dann bricht sich in der Lautlichkeit Bahn, was der ‚Logosauszeichnung‘ von Sprache und Kommunikation gerade nicht subsumierbar, durch sie nicht instrumentalisierbar ist. So ist es kaum verwunderlich, daß ein Sprach- und Kommunikationskonzept, für welches das Sprechen nicht alleine durch Regelbeschreibung rationalisierbar ist, sondern überdies noch zur Springquelle von Rationalität und rationalem Verhalten avanciert, daß ein solches Konzept ohne die Reflexion der Stimmlichkeit bestens auskommt. Wie umgekehrt: Die Stimme einzubeziehen bedeutet dann, sich an einem nicht-intellektualistischen Sprachkonzept zu orientieren. Wir haben auch schon einen Wink, wie dabei methodologisch zu verfahren ist: Eine Alternative zum kognitivistischen Sprachbild zu entwerfen, heißt zuerst einmal, eine ‚performative Revision‘ seiner methodologischen Prämissen einzuleiten.

- Das ‚Bauprinzip‘ intellektualistischer Sprachtheorien ist die Unterscheidung zwischen Schema (System, Regelwerk) und Gebrauch (Aktualisierung, Realisierung). Gemäß dieser methodologischen Prämisse gehört das Lautliche nicht zur Sprache, sondern ist ‚nur‘ das Medium zum Vollzug von Sprache, die selbst dabei als medienindifferent konzipiert ist. Die theoretische Gelenkstelle einer ‚performativen Revision‘ ist es nun, daß in ihrem Rahmen Medien eben nicht mehr marginal, vielmehr konstitutiv sind. ‚Konstitutiv‘ insofern im aktualisierenden Vollzug eines Schemas dieses Schema immer auch transformiert, unterminiert oder überstiegen wird. Die Richtung, die der kreative Überschuß des Vollzuges gegenüber dem darin realisierten Muster jeweils annehmen kann, ist aber als Potential im Medium selbst angelegt.

- Aber sind die ‚Weichen‘ eines solchen Alternativprogramms nicht schon längstens gestellt? Spätestens mit der im poststrukturalistischen Diskurs – einsetzend mit Lacan – üblich gewordenen Aufwertung des Signifikanten gegenüber dem Signifikat, ist doch eine Perspektive gewonnen, in der auch die Stimme als genuiner Bestandteil sprachlichen Geschehens rehabilitierbar ist. Das ist dann der Fall, wenn wir die Stimme als materiellen Signifikanten und den Aussagegehalt der Rede als deren Signifikat deuten. Wir brauchen doch nur ‚was ein Medium ist‘ zu identifizieren mit dem materiellen Zeichenträger – und schon ist ein bequemer Zugang gewonnen, um nahezu alle geistes- und kulturwissenschaftlichen Objekte, die doch im weitesten Sinne als ‚Zeichendinge‘ bzw. ‚symbolische Formen‘ qualifizierbar sind, in eine medientheoretische Perspektive zu rücken. Die Stimme wäre damit nicht länger als ein Außersprachliches marginalisiert, vielmehr als unverzichtbarer materieller Signifikant sprachlicher Semiosis rehabilitiert. Und doch: Dieser Weg führt noch nicht weit genug.

- Der Grund dafür ist, daß, was immer ein Medium ist, nicht aufgeht in dem, wozu ein ‚Signifkant‘ im Rahmen der semiotischen Beziehung zwischen Zeichenträger und Zeichenbedeutung dient. Oder, falls man doch das Medium irgendwie auf Seiten Signifkanten lokalisieren möchte: Das Medium ist dann gerade jene Dimension am Signifikanten, „die nicht zur Signifikation beiträgt.“ Das Medium durchbricht also das Modell der Semiosis. Medientheoretische Reflexionen erweisen sich damit als eine Möglichkeit, die Grenzen des semiotischen Paradigmas für Untersuchung und Reflexionkultureller Gegenstände auszuloten.

- Fassen wir diese Überlegungen zusammen: Die semiotische Wirkung der Stimme beruht weniger auf kodierter Zeichengebung und mehr auf unwillkürlicher Indexikalität. Die Stimme ist nicht einfach Symbol, sondern Spur von etwas; sie fungiert nicht einfach als Zeichen, vielmehr als Anzeichen. In dieser ihrer Indexikalität ist es begründet, daß die Stimme nicht nur spricht, sondern zeigt. Gemäß einer traditionellen Schematisierung unserer symbolischen Vermögen stehen uns zwei grundlegende Register der Zeichengebung zu Gebote: das ist das Diskursive und das Ikonische, das Sagen und das Zeigen, auch explizierbar als das Digitale und das Analoge. Wir sind gewohnt, die Sprache mit dem Diskursiven, dem Sagbaren, das Bild aber mit dem Ikonischen, dem Zeigbaren zu identifizieren. Wenn aber die Behauptung, daß mit der Stimme ein analogisch-indexikalisches Prinzip beim Sprechen wirksam wird, zutrifft, ergibt sich ein bemerkenswerter Umstand: Jenes physischpsychische Substrat des zum Laut geformten Schalls, das wie kein anderes in seiner zeitlichen Sukzessivität und Fluidität geeignet ist, sprachliche Materialität zu stiften, also der Sprache‚ einen Körper zu geben‘, wird als ein nicht-diskursives Anzeichen zur Bedingung der Möglichkeit zeichenhafter Diskursivität. Die Signifikanz der Lautsprache ist verwoben mit dem Signalcharakter des Lautlichen.

- Was es heißt, daß die Stimme nicht nur beiträgt zur Signifikanz der Rede, sondern diese auch durchbricht, erschließt sich erst einer Einstellung, die wir hier als ‚Negative Semiologie‘ kennzeichnen können. Die Maxime der Negativen Semiologie ist: Was die Stimme als Medium von Sprache und Kommunikation bewirkt, ist in zeichentheoretischen Termini hinreichend nicht mehr beschreibbar. Die Medienperspektive einzunehmen ist also ein Versuch, die in der Semiosis nicht aufgehenden Dimensionen der Lautlichkeit zutage treten zu lassen. Daher läuft die Medienperspektive – in letzter Konsequenz – darauf hinaus, die uns selbstverständliche Idee, sprachliches Tun mit einem Zeichenhandeln zu identifizieren, zu relativieren.

- Gehen wir noch einmal aus von der Materialität der mündliche Sprache: Es gibt eine mit und seit Aristoteles ‚definitiv‘ gewordene begriffliche Trias zur Kennzeichnung des Akustischen: psophos (lat. sonus) bedeutet Schall oder Geräusch; phoné (lat. vox) meint den sprachlichen Laut; phthongos (lat. sonus musicus) bezieht sich auf den musikalischen Ton.30 Die Unterscheidung zwischen sprachlichem Laut und musikalischem Ton ist also ein lang tradiertes Kulturgut. Aber ist in dieser Tradition nicht auch etwas verlorengegangen? Die Kunstpraxis der altgriechischen musiké vollzog und verstand sich als Einheit von Musik, Sprache und Tanz, kristallisiert im Bindeglied des Rhythmus als Ordnung einer Bewegung in der Zeit.31 Kann nun die konzeptuelle Aufspaltung der musiké in der Unterscheidung von Sprache und Musik auch als ein Reflex auf die Literalisierung der mündlichen Sprache durch das Alphabet gedeutet werden? Denn die phonetische Schrift mit ihrem erstmals durch die griechische Erfindung von Buchstaben für Vokale realisierten Anspruch, die mündliche Sprache vollständig in nicht weiter zerlegbare ’bedeutungslose‘ Elemente aufzuspalten, mithin die Sprache als eine Art von System aufzufassen, löst die lautsprachliche Schicht heraus aus einer kommunikativen Konstellation, in der Gestik, Mimik, Prosodie, Verbalität und Situationsbezug der Rede in holistischer Weise zusammen wirken. Auskristallisiert in einem allein zu den Augen sprechenden Schriftbild, kann die Sprache überhaupt erst zu einem Objekt von Beobachtung, Untersuchung und Reflexion und damit auch zu einem isolierbaren, solitären Medium der Kommunikation werden.

- Wenn es aber so ist, daß die phonetische Schrift zur Modellbildnerin ‚der‘ Sprache wird, – dann werden sich gerade im Begriff des ‚Lautes‘ bzw. des ‚Phonems‘ von Anbeginn Merkmale eingeschrieben haben, die nicht diejenigen der akustischen Stimme, vielmehr der visuellen Schrift sind. Die abendländische Konzeption vom Sprachlaut – das jedenfalls ist die Vermutung – ist geprägt von einem impliziten Skriptizismus. Wir können diesen Gedanken hier nicht weiter verfolgen. Uns kommt es nur auf eine Facette an, die darin besteht, daß mit der Skripturalisierung des Sprachlautes seine Entmusikalisierung eingeleitet ist. Mit der Dazwischenkunft der phonetischen Schrift wird die Sprache ihrer musikalischen Dimension entkleidet. In dieser Perspektive zeugt die Marginalisierung der Stimme daher auch von einer Eskamotierung – oder sollten wir sagen: Verdrängung? – des Musikalischen aus dem mündlichen Sprachgebrauch. Und umgekehrt: Eine Rehabilitierung der Stimmlichkeit heißt dann, die musikalische Dimension am und im Sprechen wiederzugewinnen. Das also, worin die ‚negative Semiologie der Stimme‘ die Semiotik der Sprache aufbricht, liegt in der Musikalität des Sprechens.