Open Access, pro und contra (tphff): Unterschied zwischen den Versionen

Anna (Diskussion | Beiträge) K (pic) |

Anna (Diskussion | Beiträge) K (→Open access policy in the EU framework programmes: format) |

||

| (4 dazwischenliegende Versionen desselben Benutzers werden nicht angezeigt) | |||

| Zeile 1: | Zeile 1: | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Bild:meup.jpg|center|400px]] [[Bild:meup3.jpg|center|400px]] | ||

== Proklamationen == | == Proklamationen == | ||

| Zeile 25: | Zeile 27: | ||

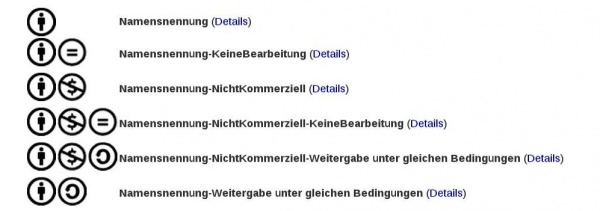

[[Bild:cc-lizenzen.jpg|center|600px]] | [[Bild:cc-lizenzen.jpg|center|600px]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Bild:3m.jpg| center| 400px]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | <div align="center"> | ||

| + | [http://rektorat.univie.ac.at/jahrespreis-2011/ Jahrespreis 2011]] | ||

| + | </div> | ||

== Contra == | == Contra == | ||

| Zeile 52: | Zeile 60: | ||

== Pro == | == Pro == | ||

| + | [http://ec.europa.eu/research/science-society/document_library/pdf_06/survey-on-open-access-in-fp7_en.pdf Survey on open access in FP7 European Commission, 7th Framework Programme, (2012)] | ||

| − | + | === Background === | |

| − | Background | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Open access refers to the practice of granting free Internet access to research outputs. The principal objective of an open access policy in the seventh framework programme (FP7) is to provide researchers and other interested members of the public with improved online access to EU-funded research results. This is considered a way to improve the EU’s return on research and development investment. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | The European Commission launched in August 2008 the open access pilot in FP7. It concerns all new projects from that date in seven FP7 research areas: energy, environment, health, information and communication technologies (cognitive systems, interaction, and robotics), research infrastructures (e-infrastructures), science in society (SiS) and socioeconomic sciences and humanities (SSH). Grant beneficiaries are expected to deposit peer-reviewed research articles or final manuscripts resulting from their projects into an online repository and make their best efforts to ensure open access to those articles within a set period of time after publication. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | 1. | + | In addition to the pilot, FP7 rules of participation also allow all projects to have open access fees eligible for reimbursement during the time of the grant agreement (1) (‘open access publishing’, also called ‘author pays’ fees). In May 2011, the Commission identified the 811 projects designated at the time and sent a questionnaire to all project coordinators in order to collect feedback on their experiences of both the implementation of the pilot and the reimbursement of open access publishing costs. A total of 194 answers were received by the end of August 2011. They provide important input for the future of the open access policy and practices in Horizon 2020 (the future EU framework programme for research and innovation), and for the preparation of a communication from the Commission and a recommendation to Member States on scientific publications in the digital age. |

| − | + | === Results === | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | === General considerations === | ||

| + | For almost 60 % of respondents who expressed an opinion, getting a common understanding in the consortium on how to best share research outcomes is considered easy or very easy. Also for 60 % of respondents with an opinion, understanding legal issues regarding copyright and licences to publish is difficult or very difficult. | ||

| + | === Self-archiving === | ||

| + | The majority of respondents find it easy or very easy to have time or manpower to self-archive peer-reviewed articles and also to inform the Commission on the failure of their best efforts to ensure open access to the deposited articles. Many respondents, however, do not know about the toolkits provided by the Commission for the purpose of offering support to beneficiaries of projects participating in the pilot. Nevertheless, when they do, the majority of respondents with an opinion find them useful. | ||

| + | Identifying a new, satisfactory publisher is rather difficult for the majority of respondents, yet 40 % of respondents with an opinion find it easy or very easy. Changing publisher or journal is also rather difficult for the majority of respondents — and is equally difficult for all FP7 research areas concerned. However, 35 % of respondents with an opinion still find it easy or very easy. Difficulties arise when the implementation of the open access mandate becomes concrete: | ||

| + | negotiating with the publishers/journals is considered difficult or very difficult by almost 75 % of respondents with an opinion. | ||

| + | Half of respondents do not know or have no opinion about which publishers to be in contact with regarding their open access publications. For the majority of respondents who had contact or intend to have contact with publishers, Elsevier comes first, closely followed by Springer. Then come Wiley-Blackwell, Nature Publishing Group and Taylor & Francis. AAAS and SAGE are also named. | ||

| + | Respondents reported a total of 534 articles deposited or to be deposited in a repository, out of which 406 are or will be open access. According to the figures given by respondents, a total of 68 articles are both deposited and made open access. Reasons given for not providing open access are firstly a publisher’s copyright agreement that does not permit deposit in a repository, followed by lack of time or resources. The largest number of articles deposited is in the FP7 research area ICT, followed by the environment and health areas. The older the project, the more articles have been deposited. | ||

| + | The EU-funded portal OpenAIRE (‘Open Access Infrastructure for Research in Europe’) (2) has supported the pilot since 2009, with mechanisms for the identification, deposit, access to and monitoring of FP7-funded articles. Half of respondents did not know about the portal before answering the questionnaire; the other half had known of it mostly through the CORDIS website and various EU-related events, although word of mouth and contact with their Commission project officers were also reported. | ||

| + | === Open access publishing (reimbursement of costs in FP7) === | ||

| + | The majority of respondents did not know about the possibility to request full reimbursement of publication costs during the lifespan of FP7 projects and only 25 % of respondents with an opinion think that the option is well-known in the consortium. Nevertheless, the older the project, the better known the option. In total, almost half of respondents replied that they intend to make use of this possibility in the future. | ||

| + | Only eight projects among all respondents reported the use of reimbursement of open access publishing so far, with total costs ranging from EUR 0 up to EUR 6 100. Seven replied they would use this possibility again, and only one was not sure. | ||

| + | When asked about financial aspects, about half of respondents are of the opinion that it is expensive (i.e. it is better to spend project money on other activities), while the other half are not of such an opinion. The vast majority of respondents are of the opinion that the possibility of reimbursement of open access publishing costs is restricted by the fact that most publishing activities occur after the project end (i.e. too late for reimbursement to be claimed). Nonetheless, almost 70 % of respondents with an opinion think that it is better to use self-archiving rather than open access publishing to satisfy the open access requirement in FP7. | ||

| + | === Open access policy in the EU framework programmes === | ||

| + | The questionnaire was taken as an opportunity to ask forward-looking questions with regards to open access to data, the best sources of information about EU policies in the field and EU support to FP7 researchers. | ||

| + | Three quarters of those respondents with an opinion would agree or strongly agree with an open access mandate for data in their research area, providing that all relevant aspects (e.g. ethics, confidentiality, intellectual property) have been considered and addressed. There are some differences depending on the FP7 research area, with most agreement in environment, ICT and e-infrastructure, and less agreement in energy. Only a small number of respondents, 13 %, have no opinion on the question. | ||

| + | The CORDIS website and the participants’ portal are considered together the best source of information to get information about future EU open access policies. EU project officers and national contact points are also highly ranked. In addition, OpenAIRE is viewed as a valuable source of information. In a last question, project coordinators were asked how the European Commission could help researchers comply with its open access policy. For many respondents, the implementation of open access can be perceived as a burden. | ||

| + | Most comments relate to the following five main categories, in order of importance: | ||

| + | *Information: The prevailing comment is, unsurprisingly, about information, the lack thereof and the best ways to inform project coordinators and the consortium on open access requirements in FP7. Information is welcome at every stage of the process, from the launch of the call to the time of contract negotiations, the signature of the grant agreement, the kick-off meeting and the commencement of the project. Many respondents stress the need to send an information pack to all applicants to FP7 calls, to make use of reminders and to inform administrative persons in charge of EU funds as well as national contact points. | ||

| + | *Publishers: There are many comments asking the European Commission to inform publishers of FP7 requirements (in fact it is already the case for all main publishers) and negotiate directly with them. In practice, there are suggestions to encourage publishers to agree on modifications to their usual rules on copyright and licences, to force them to lower their fees, or to make papers available on the project’s website regardless of the publisher’s policy. Some respondents ask if more of the workload could be put on the publishers and less on the projects while others encourage policy actions. There is also a proposal to ask the Commission to set up its own peer-reviewed open access publication mechanism. | ||

| + | *Promotion: Many comments focus on the promotion of the benefits of open access in general and on training of all partners involved (including within the Commission), with a stress on informing (sometimes reassuring) private partners that benefit from FP7 funds about the benefits of open access. | ||

| + | *Self-archiving and open access publishing: Many respondents suggest establishing a system that would fund open access publishing separately from the grant agreement and its limitation in time. There is no apparent preference for one system (self-archiving) above the other (open access publishing). | ||

| + | *Support and assistance: Many suggestions are made concerning support and assistance to grantees, such as having a Commission help desk (in fact already a feature of OpenAIRE). The Commission is asked to be concrete and detailed in its guidance, but also simple, brief, to the point and up to date. Support on how to deal with legal issues related to intellectual property rights (IPR) and licences is also welcome. | ||

| + | Additional comments focus on the enforcement and monitoring of open access requirements in FP7 and make practical suggestions with regards to repositories. | ||

| + | === Conclusions === | ||

| + | The dissemination of research results in FP7, including self-archiving and costs related to open access, is often an underestimated aspect. However, it requires specific measures and sustained investment. Despite its recognised benefits, the implementation of open access remains a challenge. Open access also raises technical questions and legal issues, linked in particular to how researchers exercise their copyright. Further difficulties are the lack of awareness of researchers and of concrete support for them to practice open access. | ||

---- | ---- | ||

[[Kategorie: freier Forschungsaustausch]] | [[Kategorie: freier Forschungsaustausch]] | ||

Aktuelle Version vom 27. Januar 2012, 09:57 Uhr

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Proklamationen

Budapester Erklärung | Berliner Erklärung

Heidelberger Appell | Aktionsbündnis Urheberrecht

Erläuterungen

Robert Darnton: Why Google Books failed (1) | Robert Darnton: Why Google Books failed (2) |Do Books have a Future? Interview mit Robert Darnton

Open Access Kommentar zu Google Search | Google Search und deutsches Bibliotheksrecht

Google Book Search (Wikisource)

Contra

Uwe Jochum: Urheber ohne Recht. Lettre International 87, Winter 2009

Damit hat er (sc. der Staat) sich freilich von vorneherein in ein doppeltes Konkurrenzverhältnis zu Google gesetzt: Er muß, will er mit Google mithalten, derselben Logik des raschen Digitalisierens großer Textmengen folgen, und er muß, anders als Google, diese Digitalisierung auf rechtskonforme Weise betreiben. Denn als Staat ist er auf das Grundrecht der Wissenschaftsfreiheit verpflichtet und muß es folglich dem Wissenschaftler überlassen, ob und wann und wie und wo dieser einen Artikel oder ein Buch veröffentlichen will. Nun braucht man nicht lange nachzudenken, um zu sehen, daß das Ziel der raschen und das Ziel der rechtskonformen Digitalisierung in einem Spannungsverhältnis stehen: Wer sich an das Recht hält und die Wissenschaftler fragt, ob sie digital publizieren wollen, muß ihr mögliches Nein akzeptieren und wird daher aufgrund dieses rechtskonformen Verfahrens niemals jenes Digitalisierungstempo vorlegen können, mit dem Google die Offentlichkeit so sehr zu beeindrucken sucht. Für den Staat heißt das, daß er entweder die Rolle des großen Innovators und Konkurrenten von Google ablegen — oder einen Weg finden muß, um sein eigenes Recht umgehen und das Digitalisierungstempo anziehen zu können.

Das Spannungsverhältnis löst sich auf, wenn man als Staat die Notwendigkeit des Fragens und damit das mögliche Nein der Autoren erst gar nicht zum Thema macht, sondern die Digitalisierung von Wissenschaft über den Aufbau einer staatlich geförderten Publikationsinfrastruktur betreibt, die dem Wissenschaftler faktisch keine Wahl mehr läßt. Dann kann man als Staat den Google-Trick des Nichtfragens, aber Machens kopieren, ohne sich dem Vorwurf des direkten Rechtsbruchs aussetzen zu müssen. Man kann dann sonntags die Wissenschaftsfreiheit predigen, um sie den Rest der Woche bequem zu ignorieren. Die Kopie dieses Google-Tricks ist das, was als "Open Access" zu beobachten ist: die großangelegte Digitalisierung wissenschaftlicher Veröffentlichungen unter Umgehung des Urheberrechts und der Wissenschaftsfreiheit, zum angeblichen Besten der Menschheit. Das müssen wir uns näher anschauen.

...

Nun mag es für einen Wissenschaftler in der Tat die größte Befriedigung darstellen, recht häufig zitiert zu werden. Aber in der Freude über häufige Zitationen darf man nicht übersehen, daß es essentiell zum wissenschaftlichen Geschäft gehört, daß der Wissenschaftler Herr über seine Publikationen bleibt, sei es, um dieses oder jenes Versehen korrigieren, sei es, um einen Text gegebenenfalls vollständig zurückziehen zu können. Ebendiese Kontrolle gesteht Open Access den Wissenschaftlern aber gerade nicht zu, denn Open Access hat sich zum Ziel gesetzt, auch die juristischen Barrieren beim Umgang mit Texten zu beseitigen, indem man den Autoren Lizenzen andient, die, wie die Creative-Commons-Lizenzen, nicht widerrufbar sind oder die, wie die GNU General Public Licence, es dem Leser eines Textes ermöglichen, die-sen Text zu verändern und den veränderten Text (unter Kenntlichmachung der veränderten Passagen) weiterzugeben. Das mag nun zwar der juristische Triumph der Rezeptionsästhetik sein, aber es hat mit dem wissenschaftlichen Publizieren, wie es seit der Antike praktiziert wurde, nicht mehr das geringste zu tun. Denn an die Stelle des von seinem Autor verantworteten letztgültigen Textes tritt ein undurchschaubares Sammelsurium von nicht mehr oder nur noch teilweise gültigen Vorab- und preprint-Versionen, hinter denen die letztgültige Textversion verschwindet; das Ganze dann potenziert durch Textversionen, in denen bastelwütige Leser in den ursprünglichen Text hineinmontiert haben, was sie für richtig halten, der originale Autor aber ausgestrichen hätte.

...

Die Umsetzung dieser Ziele stellt sich die Berliner Erklärung so vor, daß man die mit Forschungsmitteln unterstützten Forscher "darin bestärk[tJ, ihre Arbeiten gemäß den Grundsätzen des Open Access-Paradigmas [sic] zu veröffentlichen". Und weil man dann doch nicht ignorieren konnte, daß man mit der ganzen Sache quer zum geltenden Urheberrecht und der Wissenschaftsfreiheit steht, versichert man den Lesern ganz zum Schluß, daß man "die Weiterentwicklung der bestehenden rechtlichen und finanziellen Rahmenbedingungen" unterstütze, "um die Voraussetzungen für eine optimale Nutzung eines offenen Zugangs [zu wissenschaftlichen Publikationen] zu ermöglichen". Was hier als "Bestärkung" und "Weiterentwicklung" ganz zwanglos daherkommt, stellte sich freilich schon auf halbem Wege vom Jahr 2003 ins aktuelle Jahr 2009 als durchaus zwanghaft heraus. Denn als es um die konkrete Umsetzung dieser Ziele ging, las man im Jahre 2006 in einem Papier der Deutschen Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG), dem wichtigsten und finanziell potentesten Akteur der Allianz der Wissenschaftsorganisationen, plötzlich nicht nur davon, daß die Bereitschaft zum elektronischen Publizieren gemäß Open Access durch "externe Anreize" gestärkt werden sollte, man las im selben Papier nur einen Satz später das kaum kaschierte Bedauern darüber, daß die "Hochschulleitungen, die am ehesten einen gewissen (institutionellen) Druck ausüben könnten, ... bislang allerdings eher zurückhaltend [sind] bei der aktiven Propagierung elektronischer Publikationen".

Um der Sache folglich auf die Sprünge zu helfen und die nötigen "externen Anreize" in Form "eines gewissen (institutionellen) Drucks" zu setzen, stellten die Allianzorganisationen kurzerhand ihre Förderpolitik auf Open Access um. Das bedeutet konkret, daß diejenigen Forscher, die seither etwa bei der DFG einen Antrag auf Forschungsförderung stellen, mit der Erwartungshaltung der DFG konfrontiert werden, ihre geförderten Forschungsergebnisse per Open Access zu veröffentlichen. So heißt es in den DFG-Verwendungsrichtlinien für die Exzellenz-einrichtungen, mit deren Hilfe man bundesweit die berühmten wissenschaftlichen "Leuchttürme" in die graue Nacht des wissenschaftlichen Durchschnitts stellt: "Die DFG erwartet [sic], daß die mit Mitteln der Exzellenzinitiative finanzierten Forschungsergebnisse zeitnah publiziert und dabei möglichst auch digital veröffentlicht und für den entgeltfreien Zugriff im Internet (Open Access) verfügbar gemacht werden. Die entsprechenden Beiträge sollten dazu entweder zusätzlich zur Verlagspublikation in disziplinspezifische oder institutionelle elektronische Archive (Repositorien) eingestellt oder direkt in referierten bzw. renommierten Open Access Zeitschriften [sic] publiziert werden." Was diese Formulierung für einen antragswilligen Forscher bedeutet, liegt auf der Hand: Er formuliert den Antrag so, daß die "Erwartung" der DFG bedient wird, ohne lange darüber nachzudenken, ob die DFG eine solche Erwartung, die der Wissenschaftsfreiheit hohnspricht, überhaupt haben darf. Wobei die DFG, die ja als Selbstverwaltungsverein von Wissenschaft auftritt, sich jederzeit darauf berufen kann, daß das, was sie "erwartet", der selbstverwaltete Gemeinschaftswille der deutschen Forscher ist. Damit sind dann der Wille zu Open Access und der damit verbundene Abbauwille in Sachen Wissenschaftsfreiheit aufs schönste dadurch legitimiert, daß die Wissenschaftler in ihrer Gesamtheit es offenbar genau so haben wollen. Wer als Wissenschaftler dagegen Einwände erhebt und etwas anderes will, der kann diese seine Einwände und seinen eigenen Willen nur noch als ohn‑mächtigen Eigenwillen gegen einen übermächtigen Kollektivwillen stellen, um hinfort die undankbare Rolle eines wissenschaftlichen Michael Kohlhaas zu spielen. Kurz und gut: Die Wissenschaftler werden von den Allianzorganisationen mit einer Förderpolitik konfrontiert, die ihnen die freie Wahl des Publikationsweges nimmt.

Damit betreibt man letztlich die Annullierung der Wissenschaftsfreiheit, die als ein Grundrecht in unserer Verfassung implementiert ist und im Urheberrecht ihren unmittelbar rechtspraktischen Niederschlag findet. Wie weit man auf diesem Annullierungspfad bereits getrampelt ist, zeigen wiederum die Verwendungsrichtlinien Exzellenzeinrichtungen der DFG, in denen es heißt: "An Exzellenzeinrichtungen beteiligte Wissenschaftler sollten sich in Verlagsverträgen möglichst ein nicht ausschließliches Verwertungsrecht zur elektronischen Publikation ihrer Forschungsergebnisse zwecks entgeltfreier Nutzung fest und dauerhaft vorbehalten." Hier wird in Form eines „Sollens” genau das vorgetragen, was im Rahmen der Wissenschaftsfreiheit gar nicht vortragbar ist, weil das "nicht ausschließliche Verwertungsrecht" dem Wissenschaftler die Kontrolle über seine Veröffentlichungen entzieht: Texte, auf die der Urheber keine ausschließlichen Rechte mehr hat, sind von vornherein und prinzipiell Texte, die in ein Textkollektiv ... so eingebracht werden, dass das Kollektiv der Textverbraucher die maßgebliche Instanz ist und nicht der individuelle Textproduzent.

Um diesem Aberwitz ein Ende zu machen, braucht es wenig. Man muß dazu nur auf die institutionelle Position hinweisen, von der aus die Allianz der Wissenschaftsorganisationen spricht. Es handelt sich um die Position von Einrichtungen, die zu einhundert Prozent vom Staat über Steuermittel finanziert werden, so daß man erwarten sollte, daß sie als vollständig staatsfinanzierte Organisationen nicht nur eine abstrakt rechtliche, sondern auch eine konkret grundrechtskonforme Position vertreten; und das heißt in dem Kontext, um den es hier geht: daß sie die Wissenschaftsfreiheit zur obersten Maxime ihres Handelns machen. Tun sie es nicht — und sie tun es in der Tat nicht —, widersprechen sie ihrer eigenen raison d'etre, und darüber ist dann nicht mehr in weiteren schönen Worten zu diskutieren, sondern sind bloß noch konsequente Taten zu fordern. Dazu gehört, daß die Politik in Form der zuständigen Ministerien in den Allianzorganisationen nach dem Rechten schaut und eine mit dem Grundgesetz wieder zu vereinbarende Forschungsförderung durchsetzt.

Pro

Survey on open access in FP7 European Commission, 7th Framework Programme, (2012)

Background

Open access refers to the practice of granting free Internet access to research outputs. The principal objective of an open access policy in the seventh framework programme (FP7) is to provide researchers and other interested members of the public with improved online access to EU-funded research results. This is considered a way to improve the EU’s return on research and development investment.

The European Commission launched in August 2008 the open access pilot in FP7. It concerns all new projects from that date in seven FP7 research areas: energy, environment, health, information and communication technologies (cognitive systems, interaction, and robotics), research infrastructures (e-infrastructures), science in society (SiS) and socioeconomic sciences and humanities (SSH). Grant beneficiaries are expected to deposit peer-reviewed research articles or final manuscripts resulting from their projects into an online repository and make their best efforts to ensure open access to those articles within a set period of time after publication.

In addition to the pilot, FP7 rules of participation also allow all projects to have open access fees eligible for reimbursement during the time of the grant agreement (1) (‘open access publishing’, also called ‘author pays’ fees). In May 2011, the Commission identified the 811 projects designated at the time and sent a questionnaire to all project coordinators in order to collect feedback on their experiences of both the implementation of the pilot and the reimbursement of open access publishing costs. A total of 194 answers were received by the end of August 2011. They provide important input for the future of the open access policy and practices in Horizon 2020 (the future EU framework programme for research and innovation), and for the preparation of a communication from the Commission and a recommendation to Member States on scientific publications in the digital age.

Results

General considerations

For almost 60 % of respondents who expressed an opinion, getting a common understanding in the consortium on how to best share research outcomes is considered easy or very easy. Also for 60 % of respondents with an opinion, understanding legal issues regarding copyright and licences to publish is difficult or very difficult.

Self-archiving

The majority of respondents find it easy or very easy to have time or manpower to self-archive peer-reviewed articles and also to inform the Commission on the failure of their best efforts to ensure open access to the deposited articles. Many respondents, however, do not know about the toolkits provided by the Commission for the purpose of offering support to beneficiaries of projects participating in the pilot. Nevertheless, when they do, the majority of respondents with an opinion find them useful.

Identifying a new, satisfactory publisher is rather difficult for the majority of respondents, yet 40 % of respondents with an opinion find it easy or very easy. Changing publisher or journal is also rather difficult for the majority of respondents — and is equally difficult for all FP7 research areas concerned. However, 35 % of respondents with an opinion still find it easy or very easy. Difficulties arise when the implementation of the open access mandate becomes concrete: negotiating with the publishers/journals is considered difficult or very difficult by almost 75 % of respondents with an opinion.

Half of respondents do not know or have no opinion about which publishers to be in contact with regarding their open access publications. For the majority of respondents who had contact or intend to have contact with publishers, Elsevier comes first, closely followed by Springer. Then come Wiley-Blackwell, Nature Publishing Group and Taylor & Francis. AAAS and SAGE are also named.

Respondents reported a total of 534 articles deposited or to be deposited in a repository, out of which 406 are or will be open access. According to the figures given by respondents, a total of 68 articles are both deposited and made open access. Reasons given for not providing open access are firstly a publisher’s copyright agreement that does not permit deposit in a repository, followed by lack of time or resources. The largest number of articles deposited is in the FP7 research area ICT, followed by the environment and health areas. The older the project, the more articles have been deposited.

The EU-funded portal OpenAIRE (‘Open Access Infrastructure for Research in Europe’) (2) has supported the pilot since 2009, with mechanisms for the identification, deposit, access to and monitoring of FP7-funded articles. Half of respondents did not know about the portal before answering the questionnaire; the other half had known of it mostly through the CORDIS website and various EU-related events, although word of mouth and contact with their Commission project officers were also reported.

Open access publishing (reimbursement of costs in FP7)

The majority of respondents did not know about the possibility to request full reimbursement of publication costs during the lifespan of FP7 projects and only 25 % of respondents with an opinion think that the option is well-known in the consortium. Nevertheless, the older the project, the better known the option. In total, almost half of respondents replied that they intend to make use of this possibility in the future.

Only eight projects among all respondents reported the use of reimbursement of open access publishing so far, with total costs ranging from EUR 0 up to EUR 6 100. Seven replied they would use this possibility again, and only one was not sure.

When asked about financial aspects, about half of respondents are of the opinion that it is expensive (i.e. it is better to spend project money on other activities), while the other half are not of such an opinion. The vast majority of respondents are of the opinion that the possibility of reimbursement of open access publishing costs is restricted by the fact that most publishing activities occur after the project end (i.e. too late for reimbursement to be claimed). Nonetheless, almost 70 % of respondents with an opinion think that it is better to use self-archiving rather than open access publishing to satisfy the open access requirement in FP7.

Open access policy in the EU framework programmes

The questionnaire was taken as an opportunity to ask forward-looking questions with regards to open access to data, the best sources of information about EU policies in the field and EU support to FP7 researchers.

Three quarters of those respondents with an opinion would agree or strongly agree with an open access mandate for data in their research area, providing that all relevant aspects (e.g. ethics, confidentiality, intellectual property) have been considered and addressed. There are some differences depending on the FP7 research area, with most agreement in environment, ICT and e-infrastructure, and less agreement in energy. Only a small number of respondents, 13 %, have no opinion on the question.

The CORDIS website and the participants’ portal are considered together the best source of information to get information about future EU open access policies. EU project officers and national contact points are also highly ranked. In addition, OpenAIRE is viewed as a valuable source of information. In a last question, project coordinators were asked how the European Commission could help researchers comply with its open access policy. For many respondents, the implementation of open access can be perceived as a burden.

Most comments relate to the following five main categories, in order of importance:

- Information: The prevailing comment is, unsurprisingly, about information, the lack thereof and the best ways to inform project coordinators and the consortium on open access requirements in FP7. Information is welcome at every stage of the process, from the launch of the call to the time of contract negotiations, the signature of the grant agreement, the kick-off meeting and the commencement of the project. Many respondents stress the need to send an information pack to all applicants to FP7 calls, to make use of reminders and to inform administrative persons in charge of EU funds as well as national contact points.

- Publishers: There are many comments asking the European Commission to inform publishers of FP7 requirements (in fact it is already the case for all main publishers) and negotiate directly with them. In practice, there are suggestions to encourage publishers to agree on modifications to their usual rules on copyright and licences, to force them to lower their fees, or to make papers available on the project’s website regardless of the publisher’s policy. Some respondents ask if more of the workload could be put on the publishers and less on the projects while others encourage policy actions. There is also a proposal to ask the Commission to set up its own peer-reviewed open access publication mechanism.

- Promotion: Many comments focus on the promotion of the benefits of open access in general and on training of all partners involved (including within the Commission), with a stress on informing (sometimes reassuring) private partners that benefit from FP7 funds about the benefits of open access.

- Self-archiving and open access publishing: Many respondents suggest establishing a system that would fund open access publishing separately from the grant agreement and its limitation in time. There is no apparent preference for one system (self-archiving) above the other (open access publishing).

- Support and assistance: Many suggestions are made concerning support and assistance to grantees, such as having a Commission help desk (in fact already a feature of OpenAIRE). The Commission is asked to be concrete and detailed in its guidance, but also simple, brief, to the point and up to date. Support on how to deal with legal issues related to intellectual property rights (IPR) and licences is also welcome.

Additional comments focus on the enforcement and monitoring of open access requirements in FP7 and make practical suggestions with regards to repositories.

Conclusions

The dissemination of research results in FP7, including self-archiving and costs related to open access, is often an underestimated aspect. However, it requires specific measures and sustained investment. Despite its recognised benefits, the implementation of open access remains a challenge. Open access also raises technical questions and legal issues, linked in particular to how researchers exercise their copyright. Further difficulties are the lack of awareness of researchers and of concrete support for them to practice open access.