Orientierung (tphff2015): Unterschied zwischen den Versionen

Anna (Diskussion | Beiträge) K (link) |

Anna (Diskussion | Beiträge) K (headings) |

||

| Zeile 11: | Zeile 11: | ||

<br /> | <br /> | ||

| + | |||

| + | == Komplikationen == | ||

| + | |||

---- | ---- | ||

| Zeile 20: | Zeile 23: | ||

---- | ---- | ||

<br /> | <br /> | ||

| + | |||

| + | == Beispiele == | ||

=== Beiträge zur Rubrik "Großartige Sammlungen" aus Philosophie auf iTunes U === | === Beiträge zur Rubrik "Großartige Sammlungen" aus Philosophie auf iTunes U === | ||

| Zeile 100: | Zeile 105: | ||

[[Bild:Fecher-friesicke2.png|800px|center]] | [[Bild:Fecher-friesicke2.png|800px|center]] | ||

| − | == | + | == Open Access: Beispiel zum status quo == |

| − | |||

| − | |||

'''[http://sammelpunkt.philo.at Sammelpunkt. Elektronisch archivierte Theorie]''' | '''[http://sammelpunkt.philo.at Sammelpunkt. Elektronisch archivierte Theorie]''' | ||

Version vom 25. März 2015, 10:02 Uhr

Inhaltsverzeichnis

einfach offen

Ein Projekt aus dem Jahr 2006:

Zugang zum Wissen (tphff2015)

Komplikationen

- "The term open access may suggest that, like a door, a journal is open or it is not." (Willinsky, 2006, p.28)

- Offene Türen sind Einladungen und Gelegenheit zum Einbruch.

- "offen" ist eine Vokabel, die zunächst in der Objektwelt begegnet.

Beispiele

Beiträge zur Rubrik "Großartige Sammlungen" aus Philosophie auf iTunes U

Präsentation und Diskussion eines Dokumentarfilms an der Universidade de Vigo, Spanien.

Abgerufen 18.3.2015. Hochgeladen 2009.

ein offenes Geheimnis

CLoud-Dienste: Dropbox, SkyDrive (Microsoft), iCloud, Google Drive, OwnCloud. Ihre Funktion überlagert sich mit "one click hostering".

Nick Marx: Storage Wars: Clouds, Cyberlockers, and Media Piracy in the Digital Economy

- If, as Lawrence Lessig argues, every media industry is born of some form of piracy, then describing pirate practices with more nuance can provide a clearer picture of how institutionalized media powers are confronting the many challenges of the digital economy. Characterizing media piracy as partly constitutive of, rather than directly oppositional to, established industry routines allows us to see the former with the same complexity commonly afforded the latter. It also avoids reinforcing binaristic conceptions—old versus new or licit versus illicit—of how media circulate and participate in the construction of cultural discourses.

...

- In contrast to P2P communities that connect users with one another, cyberlockers are “web services that allow a user to upload and store files on dedicated, always-on servers, and then share those files with other users through a URL.” Although cyberlockers and websites with similar functionalities (like P2P file-sharing communities) have been and continue to be used for a variety of legal purposes, they have also become a haven for pirate activity. On one level, cyberlockers provide a very similar function to what P2P file-sharing communities offer. Users upload files on one end and download them on the other. On another level, cyberlockers are, technologically and industrially, an extension of current cloud-based services endorsed by the entertainment industry.

...

- Cyberlockers, by extension, remove the direct P2P element from file sharing and reinsert a distribution intermediary between industry and consumer, doing so in a manner that makes the charge of outright piracy much more muddled than it is for existing file-sharing models.

...

- For instance, almost two-thirds of the traffic using the popular P2P file-sharing protocol BitTorrent, one that accounts for nearly 18 percent of all global internet traffic, is composed of copyrighted films, television episodes, and music.16 Cyberlocker traffic from sites such as RapidShare and Megaupload accounts for 7 percent of all global internet traffic, three-quarters of which is estimated to be illegally traded content.

...

- Unlike P2P protocols, which require a separate application, only a web browser is needed for cyberlocker users to upload a file of their choice to the cyberlocker server. The cyberlocker then provides the uploading user with a URL that connects anyone clicking on it directly to the cyberlocker server. The uploader can choose to share this URL with anyone else, for private or public display. Non-paying users have restrictions placed on the size, frequency, and speeds with which they can upload or download, but users paying for premium memberships (averaging $13 per month) are granted instant and high-speed downloads to any content stored by the site.

...

- The Swiss company RapidShare, founded in 2006, provides a useful example for examining the brief history of how cyberlockers have negotiated pirate practices with licit uses. At its peak in 2009 and early 2010, the site averaged hundreds of millions of hits per month and ranked among the top fifty most-used sites on the internet, a remarkable feat when one considers that sites such as Apple’s home page, BBC Online, and Flickr also occupied spots near the low end of the top-fifty range. RapidShare offers a user- friendly interface and good storage capacity even for free accounts, but users can pay more if they want more storage capacity or quicker access to other content on the site. Crucially, though, RapidShare and many cyberlockers do not allow the content of their sites to be searched in the same way that torrent portals do. That is, there is no way to visit the RapidShare site and enter Breaking Bad or Avatar with the hope that download links to these media will appear. Instead, myriad third-party indexing websites such as FilesTube.com have sprung up that search for and collate download links from the innumerable bulletin boards, chat rooms, and web forums where users gather to talk about and share media.

...

- But the crucial difference for cyberlocker users comes in the extra step of directing this impulse into an abstracted vessel first—the cloud of storage—before it finds another individual. By inserting this intermediary into the exchange of pirated media, cyberlockers diffuse the collective claims to countervailing power made possible by P2P communities, and isolate users’ media consumption according to the commercially driven industry mandates of individual choice and control.

...

- Here it is helpful to consider cyberlocker piracy not just in the moment of transaction itself—from the user to the site to the other user—but also in terms of the structuring discourses of online commerce and their cultural contexts. RapidShare’s overtures to Hollywood production studios, and the celebrity endorsements of Megaupload, for instance, highlight the extent to which cyberlockers collapse the differences between established industry forces and pirates operating against them. The construction of this collapse beyond the realm of cyberlocker users’ everyday lived experiences—in the cloud—further removes from their minds the possibility of media piracy being a constitutive, even necessary part of emergent business models in the digital economy. When the cloud casts a shadow over not only technological innovation, but also cultural power, it becomes less and less the metaphor we imagine it to be.

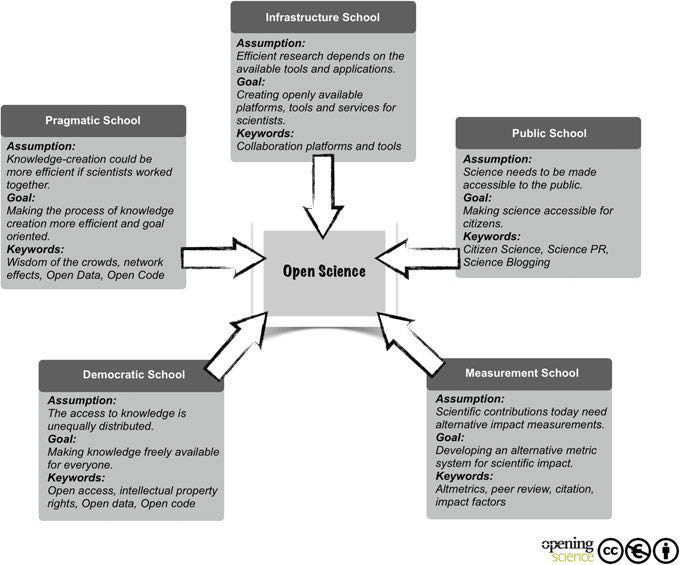

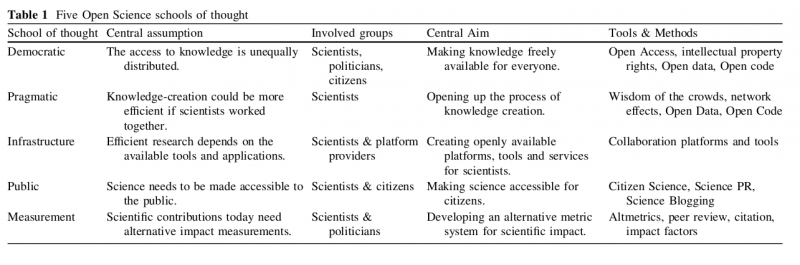

offene Wissenschaft

Benedikt Fecher, Sascha Friesicke: OPen Science: One Term, Five Schools of Thought.

in: Bartling, Sönke, Friesike, Sascha (Eds.) Opening Science. The Evolving Guide on How the Internet is Changing Research, Collaboration and Scholarly Publishing, Heidelberg 2014.

Rechtliche Information von "Springer Open"

Seite 19f.

Open Access: Beispiel zum status quo

Sammelpunkt. Elektronisch archivierte Theorie

Kollektion. Metadaten philosophischer Arbeiten in OAI-konformen elektronischen Archiven.