Die Christen (mse): Unterschied zwischen den Versionen

Anna (Diskussion | Beiträge) K (content) |

Anna (Diskussion | Beiträge) K (content) |

||

| Zeile 1: | Zeile 1: | ||

| + | [[Bild:verschwimmen.JPG|600px|center]] | ||

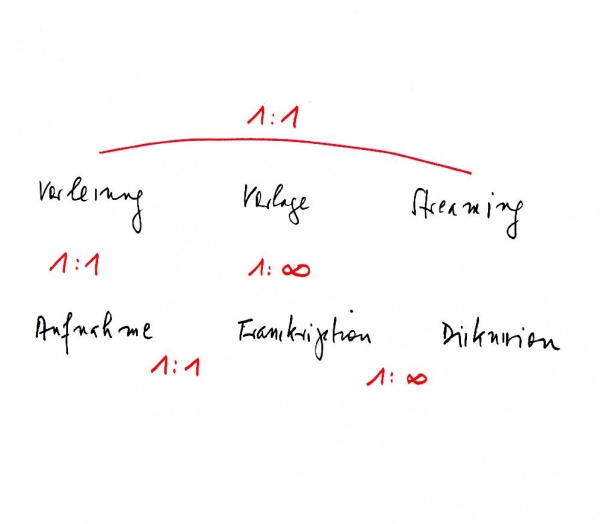

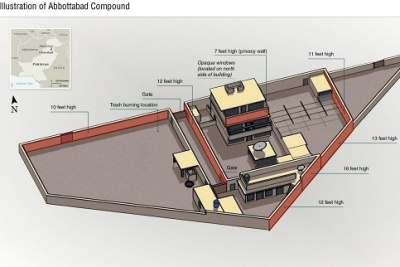

| − | [[Bild: | + | Der Ausgangspunkt bei einer Vorlesung und beim Vorlesungs-Streaming steht in der Tradition der Schulausbildung nach dem Muster der platonischen Akademie. Das Spannungsverhältnis zwischen "Kontaktstunden" und "e-Learning" ist ein später Ausläufer der mündlichen und schriftlichen Wissensvermittlung. Zu Beginn der Vorlesung habe ich darauf hingewiesen, dass die gegenwärtigen Kommunikationstechnologien diese Kontraste abschwächen. Hier sind zwei Bilder. Sie stehen für Ereignisse, welche die ganze Welt bewegt haben. Die Frage des Verhältnisses zwischen einem Ereignis und seinen Folgewirkungen ist auch ausserhalb des akademischen Kontextes zu betrachten. |

| + | |||

| + | {| | ||

| + | |[[Bild:see.jpg|400px]] | ||

| + | |[[Bild:abbo.jpg|400px]] | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | |||

| + | An einem Punkt in Raum und Zeit geschieht etwas ''von Bedeutung''. Die "Kunde" davon "pflanzt sich fort". Was sind die Bedingungen dafür, dass das geschieht? Und was bedeuten diese Bedingungen rückwirkend für das Geschehen? Die Zerstörung eines Nuklearreaktors oder die Ermordung eines Menschen sind Singularitäten, die unter Umständen in ein dichtes Netz von Informationsübermittlung Eingang finden, in dem sich die Effekte unberechenbar vervielfachen. | ||

| − | + | Zurück zu Antike. Platons Bücher haben eine weltgeschichtliche Wirkungsgeschichte. Eine ausserakademische Schlüsselrolle kommt einer anderen Lehrtätigkeit zu, die ebenfalls an der Schwelle von Mündlichkeit zur Schriftlichkeit angesiedelt ist. | |

== Das Geschehen, das Weitersagen, die Aufzeichnung == | == Das Geschehen, das Weitersagen, die Aufzeichnung == | ||

Version vom 6. Mai 2011, 08:42 Uhr

Der Ausgangspunkt bei einer Vorlesung und beim Vorlesungs-Streaming steht in der Tradition der Schulausbildung nach dem Muster der platonischen Akademie. Das Spannungsverhältnis zwischen "Kontaktstunden" und "e-Learning" ist ein später Ausläufer der mündlichen und schriftlichen Wissensvermittlung. Zu Beginn der Vorlesung habe ich darauf hingewiesen, dass die gegenwärtigen Kommunikationstechnologien diese Kontraste abschwächen. Hier sind zwei Bilder. Sie stehen für Ereignisse, welche die ganze Welt bewegt haben. Die Frage des Verhältnisses zwischen einem Ereignis und seinen Folgewirkungen ist auch ausserhalb des akademischen Kontextes zu betrachten.

|

|

An einem Punkt in Raum und Zeit geschieht etwas von Bedeutung. Die "Kunde" davon "pflanzt sich fort". Was sind die Bedingungen dafür, dass das geschieht? Und was bedeuten diese Bedingungen rückwirkend für das Geschehen? Die Zerstörung eines Nuklearreaktors oder die Ermordung eines Menschen sind Singularitäten, die unter Umständen in ein dichtes Netz von Informationsübermittlung Eingang finden, in dem sich die Effekte unberechenbar vervielfachen.

Zurück zu Antike. Platons Bücher haben eine weltgeschichtliche Wirkungsgeschichte. Eine ausserakademische Schlüsselrolle kommt einer anderen Lehrtätigkeit zu, die ebenfalls an der Schwelle von Mündlichkeit zur Schriftlichkeit angesiedelt ist.

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Das Geschehen, das Weitersagen, die Aufzeichnung

Werner H. Kelber: Jesus and Tradition: Words in Time, Words in Space in: Semeia 65. Orality and Textuality in Early Christian Literature (1995)

And yet, in order to grasp the fuller implications of hearers' participation (not simply responses!), we will in the end have to overcome our textbound thinking and come to terms with a reality that is not encoded in texts at all. It means that we must learn to think of a large part of tradition as an extratextual phenomenon. What permitted hearers to interiorize the so-called parable of the "Good Samaritan," for example, was a culture shared by speaker and hearers alike. Unless hearers have some experience or knowledge of the role of priests, Lévites, and Samaritans in society, or rather of their social construction, this parable will not strike a responsive chord with them. Whether hearers are Samaritans themselves or informed by anti-Samaritan sentiments will make a difference in the way they hear the story. Shared experiences about the dangers of traveling, the role of priests and Lévites, and the ethics of charity weave a texture of cultural commonality that makes the story resonate in the hearts and minds of hearers. Tradition in this encompassing sense is a circumambient contextuality or biosphere in which speaker and hearers live. It includes texts and experiences transmitted through or derived from texts. But it is anything but reducible to intertextuality. (S. 159)

Throughout, the underlying, nagging question has been whether the scholarly discourse of reason corresponds with the hermeneutical sensibilities of late antiquity. To be sure, serious doubts about the premises of historical criticism have been raised before. From the collapse of the liberal quest, for example, we had to learn the lesson that written language and historical actuality do not relate to each other in a one-toone relationship. What we have to learn additionally is that our understanding of the hermeneutical status and functioning of language itself is patently culture-bound. Our search for singular originality concealed behind layers of textual encumbrances reveals much about the force of our desire, but falls short of understanding the oral implementation of multioriginality in the present act of speaking. Only on paper do texts appear to relate in a one-to-one relation to other texts. The fixation on authorial intent, on language as self-legitimating discourse, on the reduction of tradition to processes of textual transmission and stratification, and on the perception of ancient chirographs as visualizable, disengaged objects opens a vast conceptual gap that separates our own typographic rationalities from ancient media sensibilities. (S. 162)

Eckpunkte zu Wort und Schrift

Walter J. Ong: Orality and Literacy London 2002 S. 70 passim

The Interiority of Sound

In treating some psychodynamics of orality, we have thus far attended chiefly to one characteristic of sound itself, its evanescence, its relationship to time. Sound exists only when it is going out of existence. Other characteristics of sound also determine or influence oral psychodynamics. The principal one of these other characteristics is the unique relationship of sound to interiority when sound is compared to the rest of the senses. This relationship is important because of the interiority of human consciousness and of human communication itself. ... To test the physical interior of an object as interior, no sense works so directly as sound. The human sense of sight is adapted best to light diffusely reflected from surfaces. (Diffuse reflection, as from a printed page or a landscape, contrasts with specular reflection, as from a mirror.) ... The eye does not perceive an interior strictly as an interior: inside a room, the walls it perceives are still surfaces, outsides. Taste and smell are not much help in registering interiority or exteriority. Touch is. But touch partially destroys interiority in the process of perceiving it. If I wish to discover by touch whether a box is empty or full, I have to make a hole in the box to insert a hand or finger. ... Hearing can register interiority without violating it. I can rap a box to find whether it is empty or full or a wall to find whether it is hollow or solid inside. ... A violin filled with concrete will not sound like a normal violin. A saxophone sounds differently from a flute: it is structured differently inside. And above all, the human voice comes from inside the human organism which provides the voice’s resonances. Sight isolates, sound incorporates.

...

By contrast with vision, the dissecting sense, sound is thus a unifying sense. A typical visual ideal is clarity and distinctness, a taking apart (Descartes’ campaigning for clarity and distinctness registered an intensification of vision in the human sensorium— Ong 1967b, pp. 63, 221). The auditory ideal, by contrast, is harmony, a putting together. Interiority and harmony are characteristics of human consciousness. The consciousness of each human person is totally interiorized, known to the person from the inside and inaccessible to any other person directly from the inside. 228, 231) and analyze other objects by reference to this experience.

...

In a primary oral culture, where the word has its existence only in sound, with no reference whatsoever to any visually perceptible text, and no awareness of even the possibility of such a text, the phenomenology of sound enters deeply into human beings’ feel for existence, as processed by the spoken word. For the way in which the word is experienced is always momentous in psychic life. The centering action of sound (the field of sound is not spread out before me but is all around me) affects man’s sense of the cosmos. For oral cultures, the cosmos is an ongoing event with man at its center. Man is the umbilicus mundi, the navel of the world (Eliade 1958, pp. 231–5, etc.). Only after print and the extensive experience with maps that print implemented would human beings, when they thought about the cosmos or universe or ‘world’, think primarily of something laid out before their eyes, as in a modern printed atlas, a vast surface or assemblage of surfaces (vision presents surfaces) ready to be ‘explored’.

...

Orality, Community and the Sacral

Because in its physical constitution as sound, the spoken word proceeds from the human interior and manifests human beings to one another as conscious interiors, as persons, the spoken word forms human beings into close-knit groups. When a speaker is addressing an audience, the members of the audience normally become a unity, with themselves and with the speaker. If the speaker asks the audience to read a handout provided for them, as each reader enters into his or her own private reading world, the unity of the audience is shattered, to be re-established only when oral speech begins again.

Writing and print isolate. There is no collective noun or concept for readers corresponding to ‘audience’. The collective ‘readership’ — this magazine has a readership of two million — is a far-gone abstraction. To think of readers as a united group, we have to fall back on calling them an ‘audience’, as though they were in fact listeners. The spoken word forms unities on a large scale, too: countries with two or more different spoken languages are likely to have major problems in establishing or maintaining national unity, as today in Canada or Belgium or many developing countries. The interiorizing force of the oral word relates in a special way to the sacral, to the ultimate concerns of existence. In most religions the spoken word functions integrally in ceremonial and devotional life. Eventually in the larger world religions sacred texts develop, too, in which the sense of the sacral is attached also to the written word. Still, a textually supported religious tradition can continue to authenticate the primacy of the oral in many ways. In Christianity, for example, the Bible is read aloud at liturgical services. For God is thought of always as ‘speaking’ to human beings, not as writing to them. The orality of the mindset in the Biblical text, even in its epistolary sections, is overwhelming (Ong 1967b, pp. 176–91). The Hebrew dabar, which means word, means also event and thus refers directly to the spoken word.

The spoken word is always an event, a movement in time, completely lacking in the thing-like repose of the written or printed word. In Trinitarian theology, the Second Person of the Godhead is the Word, and the human analogue for the Word here is not the human written word, but the human spoken word. God the Father ‘speaks’ to his Son: he does not inscribe him. Jesus, the Word of God, left nothing in writing, though he could read and write (Luke 4:16). ‘Faith comes through hearing’, we read in the Letter to the Romans (10:17). ‘The letter kills, the spirit [breath, on which rides the spoken word] gives life’ (2 Corinthians 3:6).

Words are not Signs

Jacques Derrida has made the point that ‘there is no linguistic sign before writing’ (1976, p. 14). But neither is there a linguistic ‘sign’ after writing if the oral reference of the written text is adverted to. Though it releases unheard-of potentials of the word, a textual, visual representation of a word is not a real word, but a ‘secondary modeling system’ (cf. Lotman 1977). Thought is nested in speech, not in texts, all of which have their meanings through reference of the visible symbol to the world of sound. What the reader is seeing on this page are not real words but coded symbols whereby a properly informed human being can evoke in his or her consciousness real words, in actual or imagined sound. It is impossible for script to be more than marks on a surface unless it is used by a conscious human being as a cue to sounded words, real or imagined, directly or indirectly. Chirographic and typographic folk find it convincing to think of the word, essentially a sound, as a ‘sign’ because ‘sign’ refers primarily to something visually apprehended. Signum, which furnished us with the word ‘sign’, meant the standard that a unit of the Roman army carried aloft for visual identification — etymologically, the ‘object one follows’ (Proto-Indo-European root, sekw -, to follow).

...

Our complacency in thinking of words as signs is due to the tendency, perhaps incipient in oral cultures but clearly marked in chirographic cultures and far more marked in typographic and electronic cultures, to reduce all sensation and indeed all human experience to visual analogues. Sound is an event in time, and ‘time marches on’, relentlessly, with no stop or division. Time is seemingly tamed if we treat it spatially on a calendar or the face of a clock, where we can make it appear as divided into separate units next to each other. But this also falsifies time. Real time has no divisions at all, but is uninterruptedly continuous: at midnight yesterday did not click over into today. No one can find the exact point of midnight, and if it is not exact, how can it be midnight? And we have no experience of today as being next to yesterday, as it is represented on a calendar. Reduced to space, time seems more under control — but only seems to be, for real, indivisible time carries us to real death.

Oral man is not so likely to think of words as ‘signs’, quiescent visual phenomena. Homer refers to them with the standard epithet ‘winged words’ — which suggests evanescence, power, and freedom: words are constantly moving, but by flight, which is a powerful form of movement, and one lifting the flier free of the ordinary, gross, heavy, ‘objective’ world. In contending with Jean Jacques Rousseau, Derrida is of course quite correct in rejecting the persuasion that writing is no more than incidental to the spoken word (Derrida 1976, p. 7). But to try to construct a logic of writing without investigation in depth of the orality out of which writing emerged and in which writing is permanently and ineluctably grounded is to limit one’s understanding, although it does produce at the same time effects that are brilliantly intriguing but also at times psychedelic, that is, due to sensory distortions. Freeing ourselves of chirographic and typographic bias in our understanding of language is probably more difficult than any of us can imagine, far more difficult, it would seem, than the ‘deconstruction’ of literature, for this ‘deconstruction’ remains a literary activity.

Plato, Writing and Computers

Most persons are surprised, and many distressed, to learn that essentially the same objections commonly urged today against computers were urged by Plato in the Phaedrus (274–7) and in the Seventh Letter against writing. Writing, Plato has Socrates say in the Phaedrus, is inhuman, pretending to establish outside the mind what in reality can be only in the mind. It is a thing, a manufactured product. The same of course is said of computers. Secondly, Plato’s Socrates urges, writing destroys memory. Those who use writing will become forgetful, relying on an external resource for what they lack in internal resources. Writing weakens the mind.

...

One weakness in Plato’s position was that, to make his objections effective, he put them into writing, just as one weakness in anti-print positions is that their proponents, to make their objections more effective, put the objections into print. The same weakness in anti-computer positions is that, to make them effective, their proponents articulate them in articles or books printed from tapes composed on computer terminals. Writing and print and the computer are all ways of technologizing the word. Once the word is technologized, there is no effective way to criticize what technology has done with it without the aid of the highest technology available. Moreover, the new technology is not merely used to convey the critique: in fact, it brought the critique into existence. Plato’s philosophically analytic thought, as has been seen (Havelock 1963), including his critique of writing, was possible only because of the effects that writing was beginning to have on mental processes. In fact, as Havelock has beautifully shown (1963), Plato’s entire epistemology was unwittingly a programmed rejection of the old oral, mobile, warm, personally interactive lifeworld of oral culture (represented by the poets, whom he would not allow in his Republic). The term idea, form, is visually based, coming from the same root as the Latin video, to see, and such English derivatives as vision, visible, or videotape. Platonic form was form conceived of by analogy with visible form. The Platonic ideas are voiceless, immobile, devoid of all warmth, not interactive but isolated, not part of the human lifeworld at all but utterly above and beyond it.

...

Writing is a Technology

Plato was thinking of writing as an external, alien technology, as many people today think of the computer. Because we have by today so deeply interiorized writing, made it so much a part of ourselves, as Plato’s age had not yet made it fully a part of itself (Havelock 1963), we find it difficult to consider writing to be a technology as we commonly assume printing and the computer to be. Yet writing (and especially alphabetic writing) is a technology, calling for the use of tools and other equipment: styli or brushes or pens, carefully prepared surfaces such as paper, animal skins, strips of wood, as well as inks or paints, and much more. ... . Writing is in a way the most drastic of the three technologies. It initiated what print and computers only continue, the reduction of dynamic sound to quiescent space, the separation of the word from the living present, where alone spoken words can exist.

By contrast with natural, oral speech, writing is completely artificial. There is no way to write ‘naturally’. Oral speech is fully natural to human beings in the sense that every human being in every culture who is not physiologically or psychologically impaired learns to talk. Talk implements conscious life but it wells up into consciousness out of unconscious depths, though of course with the conscious as well as unconscious co-operation of society. Grammar rules live in the unconscious in the sense that you can know how to use the rules and even how to set up new rules without being able to state what they are. Writing or script differs as such from speech in that it does not inevitably well up out of the unconscious. The process of putting spoken language into writing is governed by consciously contrived, articulable rules: for example, a certain pictogram will stand for a certain specific word, or a will represent a certain phoneme, b another, and so on.

...

Technologies are artificial, but — paradox again — artificiality is natural to human beings. Technology, properly interiorized, does not degrade human life but on the contrary enhances it. The modern orchestra, for example, is the result of high technology. A violin is an instrument, which is to say a tool. An organ is a huge machine, with sources of power—pumps, bellows, electric generators—totally outside its operator. Beethoven’s score for his Fifth Symphony consists of very careful directions to highly trained technicians, specifying exactly how to use their tools. Legato: do not take your finger off one key until you have hit the next. Staccato: hit the key and take your finger off immediately. And so on. As musicologists well know, it is pointless to object to electronic compositions such as Morton Subotnik’s The Wild Bull on the grounds that the sounds come out of a mechanical contrivance. What do you think the sounds of an organ come out of? Or the sounds of a violin or even of a whistle?

Writing is an even more deeply interiorized technology than instrumental musical performance is. But to understand what it is, which means to understand it in relation to its past, to orality, the fact that it is a technology must be honestly faced.

What is ‘Writing’ or ‘Script’?

Writing, in the strict sense of the word, the technology which has shaped and powered the intellectual activity of modern man, was a very late development in human history. Homo sapiens has been on earth perhaps some 50,000 years (Leakey and Lewin 1979, pp. 141 and 168). The first script, or true writing, that we know, was developed among the Sumerians in Mesopotamia only around the year 3500 BC (Diringer 1953; Gelb 1963). Human beings had been drawing pictures for countless millennia before this. And various recording devices or aides-mémoire had been used by various societies: a notched stick, rows of pebbles, other tallying devices such as the quipu of the Incas (a stick with suspended cords onto which other cords were tied), the ‘winter count’ calendars of the Native American Plains Indians, and so on. But a script is more than a mere memory aid. Even when it is pictographic, a script is more than pictures. Pictures represent objects. A picture of a man and a house and a tree of itself says nothing. (If a proper code or set of conventions is supplied, it might: but a code is not picturable, unless with the help of another unpicturable code. Codes ultimately have to be explained by something more than pictures; that is, either in words or in a total human context, humanly understood.) A script in the sense of true writing, as understood here, does not consist of mere pictures, of representations of things, but is a representation of an utterance, of words that someone says or is imagined to say.

...

The critical and unique breakthrough into new worlds of knowledge was achieved within human consciousness not when simple semiotic marking was devised but when a coded system of visible marks was invented whereby a writer could determine the exact words that the reader would generate from the text. This is what we usually mean today by writing in its sharply focused sense. With writing or script in this full sense, encoded visible markings engage words fully so that the exquisitely intricate structures and references evolved in sound can be visibly recorded exactly in their specific complexity and, because visibly recorded, can implement production of still more exquisite structures and references, far surpassing the potentials of oral utterance. Writing, in this ordinary sense, was and is the most momentous of all human technological inventions. It is not a mere appendage to speech.