Philosophische Schock/Therapie (OSP): Unterschied zwischen den Versionen

Anna (Diskussion | Beiträge) K (→Spaemann: space2) |

Anna (Diskussion | Beiträge) K (→Sunstein: Zitat) |

||

| Zeile 68: | Zeile 68: | ||

<br /> | <br /> | ||

| − | === Sunstein === | + | === Cass R. Sunstein === |

| + | |||

| + | '''[http://www.oup.com/us/catalog/general/subject/Law/TechnologyandTelecomsLaw/?view=usa&ci=9780195189285 Exzerpt aus: | ||

| + | Infotopia. How Many Minds Produce Knowledge, S. 200f, 217f]''' | ||

| − | |||

What about deliberation? It is tempting to think that deliberating groups will do better than statistical groups. In such groups, the exchange of perspectives and reasons might ensure that the truth will emerge. But deliberation contains a serious risk: People may not say what they know, and so the information contained in the group as a whole may be neglected or submerged in discussion. Economic incentives reduce this risk; so, too, with the set of norms that underlie open source software and Wikipedia. But we have seen that there is no systematic evidence that deliberating groups will arrive at the truth. On the contrary, it is not even clear that deliberating groups will do better than statistical groups. Sometimes they do, especially on eureka-type problems, where the answer, once announced, appears correct to all. But when the answer is not obviously right, and when individual members tend toward a bad answer, the group is likely to do no better than a statistical group. It might even do worse. The results include many failures in both business and governance. | What about deliberation? It is tempting to think that deliberating groups will do better than statistical groups. In such groups, the exchange of perspectives and reasons might ensure that the truth will emerge. But deliberation contains a serious risk: People may not say what they know, and so the information contained in the group as a whole may be neglected or submerged in discussion. Economic incentives reduce this risk; so, too, with the set of norms that underlie open source software and Wikipedia. But we have seen that there is no systematic evidence that deliberating groups will arrive at the truth. On the contrary, it is not even clear that deliberating groups will do better than statistical groups. Sometimes they do, especially on eureka-type problems, where the answer, once announced, appears correct to all. But when the answer is not obviously right, and when individual members tend toward a bad answer, the group is likely to do no better than a statistical group. It might even do worse. The results include many failures in both business and governance. | ||

| − | But my central goal has not been to criticize deliberation as such. The discussion of the newer methods for aggregating dispersed | + | |

| + | But my central goal has not been to criticize deliberation as such. The discussion of the newer methods for aggregating dispersed information — prediction markets, wikis, open source software, and blogs — raises an important question: How can deliberating groups counteract the problems I have emphasized? The basic goal should be to increase the likelihood that deliberation will do what it is supposed to do: elicit information, promote creativity, improve decisions. It is possible to draw many lessons from an understanding of alternative ways of obtaining the views of many minds. | ||

We have seen that wikis and open source software work because people are motivated to contribute to the ultimate product. We have also seen that prediction markets do well because they create material incentives to get the right | We have seen that wikis and open source software work because people are motivated to contribute to the ultimate product. We have also seen that prediction markets do well because they create material incentives to get the right | ||

answer. In deliberating groups, by contrast, mistakes often come from informational and reputational pressure. If deliberating groups are to draw on the successes of markets, open source software, and wikis, then the solution is simple: Groups should take firm steps to increase the likelihood that people will disclose what they know. | answer. In deliberating groups, by contrast, mistakes often come from informational and reputational pressure. If deliberating groups are to draw on the successes of markets, open source software, and wikis, then the solution is simple: Groups should take firm steps to increase the likelihood that people will disclose what they know. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | Deliberating groups may not be willing or able to provide economic rewards, as markets do, but they should attempt to create their own incentives for disclosure. Social norms are what make wikis work (recall Wikiquette), and they are crucial here. If people are asked to think critically rather than simply to join the group, and they are told that the group seeks and needs individual contributions, then disclosure is more likely. Consider here a fundamental redefinition of what it means to be a team player. Frequently, a team player is thought to be someone who does not upset the group's consensus. But it would be possible, and a lot better, to understand team players as those who increase the likelihood that the team will be right — if necessary, by disrupting the conventional wisdom. | ||

| + | The point applies to many organizations, including corporate boards. In the United States, the highest-performing companies tend to have "extremely contentious boards that regard dissent as an obligation" and that "have a good fight now and then."' On such boards, "even a single dissenter can make a huge difference." | ||

| + | |||

| + | ... | ||

| + | |||

| + | Is human knowledge a wild? What is known is certainly a product of countless minds, constantly adding to existing information. Each of us depends on those who came before. Sir Isaac Newton famously captured the point, writing in 1676 to fellow scientist Robert Hooke, "What Descartes did was a good step. You have added much. . . . If I have seen further it is by standing on the shoulders of giants." | ||

| + | |||

| + | Biology, chemistry, physics, economics, psychology, linguistics, history, and many other fields are easily seen as large wikis, in which existing entries, reflecting the stock of knowledge, are "edited" all the time. But this is only a metaphor. No wiki reliably captures any single field, and it is impossible to find a global wiki that contains all of them. And it is easy to find disagreement across human communities about what counts as knowledge within relevant fields. A little example: As a visitor to China in the late 1980s, I was taken by my host to a museum in Beijing, where we came across an exhibit about Genghis Khan. Seeing that name, and without stopping to think, I remarked, "He was a terrible tyrant." My host responded, politely but with conviction, "No, he was a great leader." Trying to recover from my faux pas, I promptly said, by way of excuse, "In school in the United States, we are taught that he was a terrible tyrant." My host replied, also by way of excuse, "In school in China, we are taught that he was a great leader." | ||

| + | |||

| + | Notwithstanding persistent disagreements, new technologies are making it stunningly simple for each of us to obtain dispersed information — and to harness that information, and dispersed creativity as well, for the development of beneficial products and activities. It is child's play not only to find facts, but also to find people's evaluations of countless things, including medicine, food, films, books, cars, law, and history itself. (If you'd like to learn more about Genghis Khan, and about why my Chinese host and I disagreed about him, have a quick look under "Genghis Khan" in Wikipedia.) | ||

| + | It is tempting to think that if many people believe something, there is good reason to assume that they are right. How can many people be wrong? One of my main goals has been to answer that question. People influence one another, and the errors of a few can turn into the errors of the many. Sometimes large groups live in information cocoons. Sometimes diverse people end up occupying echo chambers simply because of social dynamics. Governments no less than educational institutions and businesses fail as a result. I have tried to explain how this is possible. | ||

| − | + | At the same time, groups and institutions often benefit from widely dispersed knowledge and from the fact that countless people have their own relevant bits of information. For many organizations, and for private and public institutions alike, the key task is to obtain and aggregate the information that people actually hold. We have seen many possible methods. Polls might be taken. People might deliberate. Markets might be used to aggregate preferences and beliefs. Dispersed pieces of information, reflecting dispersed creativity, might be collected through the different methods represented by wikis, open source software, and blogs. Because of the Internet, diverse people, with their own knowledge, are able to participate in the creation of prices, products, services, reports, evaluations, and goods, often to the benefit of all. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | At the same time, groups and institutions often benefit from widely dispersed knowledge and from the fact that countless people have their own relevant bits of information. For many organizations, and for private and public institutions alike, the key task is to obtain and aggregate the information that people actually hold. We have seen many possible methods. Polls might be taken. People might deliberate. Markets might be used to aggregate preferences and beliefs. Dispersed pieces of information, reflecting dispersed creativity, might be collected through the different methods represented by wikis, open source software, and blogs. Because of the Internet, diverse people, with their own knowledge, are able to participate in the creation of prices, products, services, reports, evaluations, and goods, often to the benefit of all | ||

| − | + | Some people are using the Internet to create a kind of Daily Me, in the form of a personalized communications universe limited to congenial points of view. But the more important development is the emergence of a Daily Us, a situation in which people can obtain immediate access to information held by all or at least most, and in which each person can instantly add to that knowledge. To an increasing extent, this form of information aggregation is astonishingly easy. It is transforming businesses, governments, and individual lives. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | <br /> | ||

=== [[Steve Fuller: Knowledge as Product and Property (BW)]] === | === [[Steve Fuller: Knowledge as Product and Property (BW)]] === | ||

Version vom 30. Januar 2009, 07:23 Uhr

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Wolfgang Kersting

Exzerpt aus: "Platons 'Staat'", S. 192ff

Die Bestimmung des Philosophen (474d-480a)

Sokrates beginnt seine Charakterisierung des Philosophen mit einer semantischen Erinnerung. Ein Philosoph ist, wie schon die Bezeichnung verrät, ein Weisheitsliebender; und sofern er wirklich ein Liebender ist, ist er ganz erfüllt von dem Verlangen nach dem Begehrten, findet auch nicht eher Ruhe, als bis er das Verlangte ganz und ungeschmälert sein eigen nennen kann. Und sofern er Weisheit und Wissen begehrt, wirft er sich voller Lernlust in jede Wissenschaft. Nicht jeder jedoch, der neugierig ist und aufgeschlossen, der erlebnishungrig Erfahrungen sammelt, die Augen aufmacht und die Ohren aufsperrt, ist weisheitsliebend zu nennen. Die „Schaulustigen” etwa und die „Hörbegierigen” sind keinesfalls zu den Weisheitsliebenden zu zählen. Denn nur solche lieben die Weisheit, die „die Wahrheit zu schauen begierig sind”, die Wahrheit aber ist weder mit den Augen noch mit den Ohren zu erfassen. Sie entzieht sich der Wahrnehmung und sinnlichen Erfahrung. Den Philosophen muß die Weisheitsliebe also über die Welt des Sinnlichen hinaustreiben.

Wenn aber Wahrheitserkenntnis nicht durch sinnliche Erfahrung zu gewinnen ist, welcher Art ist philosophisches Wissen dann? Und wenn sich philosophisches Wissen nicht mit sinnlichen Gegenständen beschäftigt, womit beschäftigt es sich dann? Mit Ideen und Wesensbestimmungen, sagt Platon, etwa mit der Idee des Schönen oder dem Wesen der Gerechtigkeit. Die Idee des Schönen ist von den vielen schönen Dingen, die Schaulustige und Hörbegierige erfreuen, verschieden; sie existiert unabhängig von den vielen schönen Gegenständen und kann zum Gegenstand einer eigenständigen Erkenntnis gemacht werden. Der Philosoph interessiert sich nicht für schöne Dinge, er trachtet danach, „das Wesen des Schönen selbst zu schauen und sich daran zu erfreuen” (476b). Und nur Philosophen sind zu einer solchen Ideenschau fähig, nur sie sind imstande, „sich dem Schönen selbst zuzuwenden und es rein für sich zu schauen”. Die anderen werden nie über das Niveau der Schaulustigen und Hörbegierigen hinausgehen, werden immer nur „für schöne Stimmen, Farben, Gestalten” schwärmen, nie aber mit ihrem Geist das Schöne an sich erfassen können.

Aber gibt es das Schöne überhaupt? Existiert das Allgemeine? Ist es sinnvoll, neben den in Raum und Zeit existierenden, wahrnehmbaren Gegenständen ap, bp, cp, ... np einen nicht sinnlich wahrnehmbaren, nicht in Raum und Zeit existierenden und nur geistig erfaßbaren Gegenstand P anzunehmen? Sind diese P-Gegenstände, diese Ideen und Wesenheiten, nicht unzulässige Vergegenständlichungen der Prädikate, mit deren Hilfe wir Gegenstände klassifizieren und damit von anderen Gegenständen unterscheiden? Um Platons Ideenlehre besser zu verstehen, ist ein sprachphilosophischer Zugang empfehlenswert. Aus sprachphilosophischer oder formal semantischer Perspektive läßt sich die Ideenlehre als Antwort auf die Frage nach dem Verstehen von generellen Termen oder Prädikaten lesen. Zu wissen, was `schön' bedeutet, heißt nach Platon dann, den Gegenstand zu kennen, auf den sich `schön' bezieht; genauso wie die Bedeutung eines Eigennamens zu kennen ja bedeutet, den Gegenstand (Person, Tier, Stadt usf.) zu kennen, auf den sich der Eigenname bezieht. Die Ideenlehre basiert demzufolge auf einer gegenstandstheoretischen Semantik, die die Bedeutung sprachlicher Ausdrücke als Gegenstandsbezug expliziert und das Bedeutungsverstehen somit als Kenntnis der Gegenstände, auf die sich die sprachlichen Ausdrücke beziehen, auslegt: ich verstehe einen Ausdruck, wenn ich den Gegenstand kenne, für den er steht. Nun haben wir zum einen sprachliche Ausdrücke, mit denen wir uns auf Dinge in Raum und Zeit beziehen, um sie zu identifizieren: Eigennamen, deiktische Ausdrücke und Kennzeichnungen, wir haben aber auch sprachliche Ausdrücke, mit denen wir diese Dinge beschreiben. Ausdrücke der ersten Art sind singuläre Termini, Ausdrücke der zweiten Art sind generelle Termini oder Prädikate. Wir verwenden Prädikate, um etwas von den Gegenständen, auf die wir uns zum Zwecke ihrer Identifizierung mittels singulärer Terme beziehen, auszusagen, um sie zu klassifizieren und dadurch von anderen Gegen-ständen zu unterscheiden. Wenn aber nun die Bedeutung sprachlicher Ausdrücke nicht durch ihre semantische Funktion innerhalb eines prädikativen Satzes bestimmt wird, sondern durch den Gegenstand, für den sie stehen, dann benötigen wir zwei Klassen von Gegenständen: zum einen Gegenstände, auf die wir uns mit Hilfe der singulären Termini beziehen, zum anderen Gegenstände, die den generellen Termini Bedeutung verleihen. Erstere sind (zumeist, aber nicht notwendigerweise) Gegenstände der sinnlichen Wahrnehmung, Dinge in Raum und Zeit, letztere sind hingegen notwendigerweise nie Gegenstände der sinnlichen Wahrnehmung. Denn neben den vielen schönen Dingen finden wir ebensowenig die Schönheit als weiteres Ding vor, wie wir neben den vielen dreieckigen Dingen die Dreieckigkeit oder neben den vielen Hunden das Hundsein als weiteres Ding vorfinden. Die Schönheit ist kein schönes Ding und das Hundsein ist kein Hund.

...

Denn da gibt es auf der einen Seite die vielen Meinungen über Gerechtigkeit oder Frömmigkeit oder Wahrheit und auf der anderen Seite das Wissen des Philosophen; und dieses Philosophenwissen ist nach Platon eben ein unfehlbares geistiges Erfassen des Gegenstandes `Wahrheit', `Frömmigkeit', `Gerechtigkeit' in seinem Ansich-sein und unwandelbaren Selbstsein. Diese Problemsituation wird jedoch durch Platons leichthändiges Analogisieren verschleiert; die parallelisierten und sich wechselseitig erläuternden Unterschiede zwischen Sinnlichkeit und Geist, Dingen und Ideen, Unwirklichkeit und Wirklichkeit, Meinung und Erkenntnis, Fürwahrhalten und Wahrheit sind ihrerseits nicht fein genug und verwischen für ein angemessenes Problemverständnis wichtige Differenzen. Denn es ist natürlich ein beträchtlicher Unterschied zwischen Dingwahrnehmung einerseits und intuitiven Meinungen und common-sense-Überzeugungen über Schönheit, Gerechtigkeit und Wahrheit andererseits. Dieser Unterschied muß jedoch marginalisiert werden, wenn das überlegene philosophische Wahrheitswissen als geistiges Erfassen von Ideen, Allgemeingegenständen, gegenständlichen Korrelaten philosophisch interessanter Prädikatsbestimmungen ausgelegt wird und damit dem entsprechenden inferioren common-sense-Wissen ebenfalls ein angemessener Gegenstand zugeordnet werden muß. Dieser kann aber nur das Sinnending in Raum und Zeit sein.

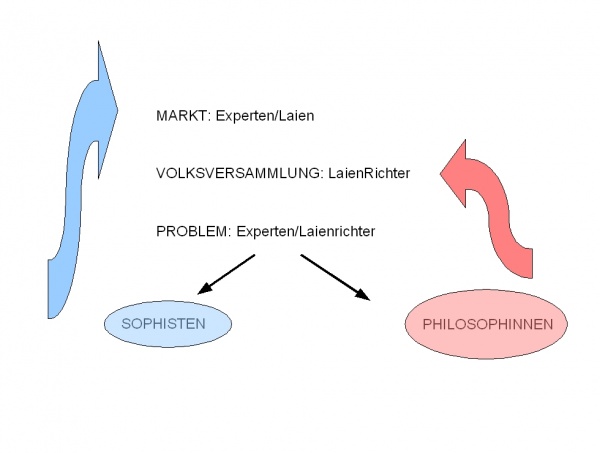

Somit ist die gegenstandstheoretische Semantik der generellen Termini heimlich dafür verantwortlich, daß der eigentliche Problemkern verhüllt wird. Denn was will Sokrates, der auf dem Marktplatz mit den Meinungsliebhabern und Sophisten konkurrierende Philosoph, eigentlich wissen? Doch wohl nichts anderes als dies: können wir die vielen, subjektiv gefärbten und kulturell codierten Gerechtigkeitskonzepte, Schönheitsvorstellungen, Wahrheitsverständnisse, Tugendüberzeugungen zugunsten einer objektiven, sich selbst als wahr und zeitlos gültig ausweisenden Erkenntnis der Natur und des Wesens der Gerechtigkeit, Schönheit, Wahrheit und der einzelnen Tugend überwinden und somit die gesellschaftlichen Auslegungskontroversen und Interpretationsstreitigkeiten über die Bedeutung der für jeden einzelnen Menschen wie für das menschliche Zusammenleben wichtigen Ordnungs- und Orientierungsbegriffe durch die Autorität des Wissens befrieden?

Plato, Politeia, 495b - 496a

Während nun einerseits diese auf jene Weise entarteten Abtrünnigen der wahren Wissenschaft, deren nächste Angehörige sie ist, eben darum, weil sie sie sitzen und im Stiche lassen, ihrerseits kein ihren Anlagen entsprechendes, wahres Leben führen, drängen sich ihr, wie einer von ihren nächsten Verwandten verlassenen Waise, andere Unberufene auf und hängen ihr dann dadurch solche Schmach und Schande an, wie sie deiner Aussage nach von ihren Anklägern vorgeworfen werden, von denen, die sich tiefer mit ihr einließen, wäre ein Teil zu nichts nütze, der größte Teil sogar verdiente das größte Unglück.

Ja, versetzte er, das sind die Äußerungen, die getan werden.

Und sie werden ganz mit Recht getan, erwiderte ich. Wenn nämlich andere Menschen sehen, daß dieser Platz leer steht und schöne Titel und Würden mit sich bringt, so springen, wie die Zuchthäusler in die heiligen Freistätten entlaufen, ebenso freudig aus ihren Alltagsberufen in das Bereich der Wissenschaft alle jene, die etwa im beschränkten Kreise ihres ursprünglichen Handwerks die Nase etwas hoch tragen. Denn der Wissenschaft, wenngleich sie im erwähnten schlimmen Zustande sich befindet, bleibt doch, wenigstens im Vergleich zu den übrigen Professionen, noch ein Ansehen übrig, das alle überstrahlt. Danach trachten nun bekanntlich die meisten, obgleich sie erstlich schon von Natur unvollkommene Anlagen haben und dann auch unter dem Drucke ihrer Berufe und Handwerke infolge der Stubenhockereien ebenso hinsichtlich ihrer Seelen zusammengeschrumpft und ausgemergelt sind, wie sie auch schon am Körper die Zeichen der Verkrüppelung tragen, oder ist das nicht eine notwendige Folge?

Ja, sicher, sagte er.

Gewähren denn nun, sprach ich, jene Leute wohl einen anderen Anblick als etwa ein zu einem Sümmchen Geld gekommener Gesell in einer Schmiede, neulich erst der Sklavenkette entwischt, jetzt aber in einem Bade rein gewaschen, in ein neues Gewand gekleidet, wie ein Bräutigam herausgeputzt und bereit, die Tochter seines Herrn zu heiraten, weil sie verarmt und von ihren nächsten Verwandten verlassen ist?

Kein sehr verschiedener Anblick, sagte er.

Was für Geburten müssen nun solche Leute hervorbringen? Nicht bastardartiges und schlechtes Zeug?

Ganz notwendig.

Nun hiervon die Anwendung: Wenn Leute, die für eine höhere Bildung gar keine Fähigkeiten haben, ohne die gehörige Ebenbürtigkeit sich mit dieser verehelichen, was für Hirngeburten und Ansichten müssen diese dann erzeugen? Nicht wohl solche, die in Wahrheit den Namen Sophistereien verdienen, und was gar keine Spur eines edlen Ursprungs und auch nicht den Wert eines gründlichen Nachdenkens an sich trägt?

Ja, das allerdings, sagte er.

Spaemann

Exzerpt aus: Robert Spaemann: Die Philosophenkönige (Buch V 473b-Vl504a) S.169f]

Warum kann nach Platons Ansicht, für die vieles spricht, auch eine Demokratie nur dann stabil und für Menschen wohltätig sein, wenn die Seelen ihrer Bürger nicht selbst „demokratisch” sind, wenn sie selbst nicht „Demokratisierung” zum Lebensinhalt macht, sondern wenn in ihren Mythen der abwesende König anwesend bleibt? (Der Ursprungsmythos der athenischen Demokratie war die Geschichte des Königs Kodros, der sich für die Stadt opferte, so daß niemand würdig war, sein Nachfolger zu werden.)

Es geht bei den Philosophenkönigen um das Grundproblem der Legitimität politischer Herrschaft. Das Problem stellt sich gerade wegen der Asymmetrie von Staat und Seele. Die Herrschaft der Vernunft in der Seele bedarf keiner Legitimation, weil sie physei ist. Die Vernunft ist von Natur das hegemonikon. Wenn sie herrscht, hat der Mensch das Bewußtsein, frei und befreundet mit sich selbst zu sein. Er selbst ist es, der „sich” regiert. Er tut, was er will, weil er weiß, was er will. Im Unterschied dazu ist Herrschaft im Staat deshalb ein Problem, weil hier nicht Vernunft über das Begehren herrscht, sondern Menschen über andere Menschen, die doch ihrerseits auch, wenn auch in geringerem Maß, vernünftige Wesen sind. Das Problem liegt darin, daß, wie es im Politikos heißt, die Hirten der Polis eben nicht Schafe hüten, sondern derselben Art angehören wie die Herde (Pol. 275b).

Nun ist es charakteristisch für die Platonische und, mit Einschränkungen, auch für die Aristotelische Staatsphilosophie ebenso wie für die ganze spätere naturrechtliche Tradition, daß die Legitimation von Herrschaft in letzter Instanz nicht eine formale, verfahrensrechtliche ist, sondern eine inhaltliche. Formale Verfahren legitimieren nicht, sondern bedürfen selbst der Legitimation. Und ihre einzige Legitimation besteht darin, daß sie, aufs Ganze gesehen, inhaltlich die relativ gerechtesten Resultate gewährleisten. Wenn sie ein offensichtlich schlechtes Resultat produzieren, muß dieses korrigiert werden. So kennen mittelalterliche Wahlordnungen – im Anschluß an die Ordnung der Abtwahl in der Regel des heiligen Benedikt – den Begriff des „gesünderen Teils”, der savior pars, deren Sache es sein kann, die Entscheidung einer korrupten oder notorisch unweisen Mehrheit zu korrigieren. Uns erscheint das befremdlich. Wir kennen so etwas in der jüngeren Geschichte nur noch aus Vorgängen in der kommunistischen Partei, die ja ihren Herrschaftsanspruch selbst überhaupt nicht formal, sondern nur durch einen materialen Wahrheitsanspruch begründete. Aber aus platonischer Perspektive ist schon diese Analogie unzulässig, weil sie ihrerseits formal ist und von inhaltlichen Differenzen absieht.

...

'Weil die menschlichen Hirten derselben Art angehören wie die Herde, sind sie eigentlich zur Herrschaft gar nicht befugt, sondern nur der Gott, „weil er allein nach Art und Weise der Hirten für die menschliche Erhaltung Sorge trägt” (Pol. 275b). Der Satz Lincolns „No man is good enough to govern another man without that others consent” steht ebenso in platonischer Tradition wie seine Voraussetzung: „the nation under God”. Jede menschliche Herrschaft bedeutet Fremdbestimmung. So sah es Thrasymachos im I. Buch der Politeia, wenn er betont, daß jeder Hirt zum eigenen Vorteil regiert. Denn jeder handelt zum eigenen Vorteil, darüber besteht in der Antike Konsens. Darum müssen im gemischten Regime, wie es die Nomoi vorsehen, die Interessen aller repräsentiert sein, und es muß die akkumulierte Erfahrungsweisheit über das Zuträgliche ihren Niederschlag in Gesetzen finden. Allerdings können solche Gesetze auf die Länge das Wohl der Polis nicht sichern, so wenig wie schriftlich fixierte Kunstregeln, hinter denen nicht mehr ein Wissen von der Funktion der herzustellenden Gegenstände steht (vgl. Pol. 297d–300c). Der Informationsverlust ist unvermeidlich.

Anders wäre es, wenn jemand ein wirkliches Wissen über das Zuträgliche besäße. Solchem Wissen müßte die bloße Erfahrungsweisheit der Gesetze weichen. Die Befürchtung, er würde seinen Vorteil auf Kosten der Regierten suchen, wäre hinfällig. Denn wem sich das Gute selbst wirklich gezeigt hat, der weiß, daß es wesentlich das Gemeinsame ist (Gorg. 505e). Indem er das Wohl der Regierten besorgt, tut er das Beste für sich selbst, denn jede Kunst ist dem, der sie hat, zuträglich, weil sie ihn vervollkommnet (Rep. 342c).

Cass R. Sunstein

[http://www.oup.com/us/catalog/general/subject/Law/TechnologyandTelecomsLaw/?view=usa&ci=9780195189285 Exzerpt aus: Infotopia. How Many Minds Produce Knowledge, S. 200f, 217f]

What about deliberation? It is tempting to think that deliberating groups will do better than statistical groups. In such groups, the exchange of perspectives and reasons might ensure that the truth will emerge. But deliberation contains a serious risk: People may not say what they know, and so the information contained in the group as a whole may be neglected or submerged in discussion. Economic incentives reduce this risk; so, too, with the set of norms that underlie open source software and Wikipedia. But we have seen that there is no systematic evidence that deliberating groups will arrive at the truth. On the contrary, it is not even clear that deliberating groups will do better than statistical groups. Sometimes they do, especially on eureka-type problems, where the answer, once announced, appears correct to all. But when the answer is not obviously right, and when individual members tend toward a bad answer, the group is likely to do no better than a statistical group. It might even do worse. The results include many failures in both business and governance.

But my central goal has not been to criticize deliberation as such. The discussion of the newer methods for aggregating dispersed information — prediction markets, wikis, open source software, and blogs — raises an important question: How can deliberating groups counteract the problems I have emphasized? The basic goal should be to increase the likelihood that deliberation will do what it is supposed to do: elicit information, promote creativity, improve decisions. It is possible to draw many lessons from an understanding of alternative ways of obtaining the views of many minds. We have seen that wikis and open source software work because people are motivated to contribute to the ultimate product. We have also seen that prediction markets do well because they create material incentives to get the right answer. In deliberating groups, by contrast, mistakes often come from informational and reputational pressure. If deliberating groups are to draw on the successes of markets, open source software, and wikis, then the solution is simple: Groups should take firm steps to increase the likelihood that people will disclose what they know.

Deliberating groups may not be willing or able to provide economic rewards, as markets do, but they should attempt to create their own incentives for disclosure. Social norms are what make wikis work (recall Wikiquette), and they are crucial here. If people are asked to think critically rather than simply to join the group, and they are told that the group seeks and needs individual contributions, then disclosure is more likely. Consider here a fundamental redefinition of what it means to be a team player. Frequently, a team player is thought to be someone who does not upset the group's consensus. But it would be possible, and a lot better, to understand team players as those who increase the likelihood that the team will be right — if necessary, by disrupting the conventional wisdom. The point applies to many organizations, including corporate boards. In the United States, the highest-performing companies tend to have "extremely contentious boards that regard dissent as an obligation" and that "have a good fight now and then."' On such boards, "even a single dissenter can make a huge difference."

...

Is human knowledge a wild? What is known is certainly a product of countless minds, constantly adding to existing information. Each of us depends on those who came before. Sir Isaac Newton famously captured the point, writing in 1676 to fellow scientist Robert Hooke, "What Descartes did was a good step. You have added much. . . . If I have seen further it is by standing on the shoulders of giants."

Biology, chemistry, physics, economics, psychology, linguistics, history, and many other fields are easily seen as large wikis, in which existing entries, reflecting the stock of knowledge, are "edited" all the time. But this is only a metaphor. No wiki reliably captures any single field, and it is impossible to find a global wiki that contains all of them. And it is easy to find disagreement across human communities about what counts as knowledge within relevant fields. A little example: As a visitor to China in the late 1980s, I was taken by my host to a museum in Beijing, where we came across an exhibit about Genghis Khan. Seeing that name, and without stopping to think, I remarked, "He was a terrible tyrant." My host responded, politely but with conviction, "No, he was a great leader." Trying to recover from my faux pas, I promptly said, by way of excuse, "In school in the United States, we are taught that he was a terrible tyrant." My host replied, also by way of excuse, "In school in China, we are taught that he was a great leader."

Notwithstanding persistent disagreements, new technologies are making it stunningly simple for each of us to obtain dispersed information — and to harness that information, and dispersed creativity as well, for the development of beneficial products and activities. It is child's play not only to find facts, but also to find people's evaluations of countless things, including medicine, food, films, books, cars, law, and history itself. (If you'd like to learn more about Genghis Khan, and about why my Chinese host and I disagreed about him, have a quick look under "Genghis Khan" in Wikipedia.)

It is tempting to think that if many people believe something, there is good reason to assume that they are right. How can many people be wrong? One of my main goals has been to answer that question. People influence one another, and the errors of a few can turn into the errors of the many. Sometimes large groups live in information cocoons. Sometimes diverse people end up occupying echo chambers simply because of social dynamics. Governments no less than educational institutions and businesses fail as a result. I have tried to explain how this is possible.

At the same time, groups and institutions often benefit from widely dispersed knowledge and from the fact that countless people have their own relevant bits of information. For many organizations, and for private and public institutions alike, the key task is to obtain and aggregate the information that people actually hold. We have seen many possible methods. Polls might be taken. People might deliberate. Markets might be used to aggregate preferences and beliefs. Dispersed pieces of information, reflecting dispersed creativity, might be collected through the different methods represented by wikis, open source software, and blogs. Because of the Internet, diverse people, with their own knowledge, are able to participate in the creation of prices, products, services, reports, evaluations, and goods, often to the benefit of all.

Some people are using the Internet to create a kind of Daily Me, in the form of a personalized communications universe limited to congenial points of view. But the more important development is the emergence of a Daily Us, a situation in which people can obtain immediate access to information held by all or at least most, and in which each person can instantly add to that knowledge. To an increasing extent, this form of information aggregation is astonishingly easy. It is transforming businesses, governments, and individual lives.

Steve Fuller: Knowledge as Product and Property (BW)

zurück zu Open Source Philosophie (Vorlesung Hrachovec, Winter 2008)